Adolf Dirr's

extremely obscure article on

TREPANATION

as a form of

LEGAL EVIDENCE

in the Caucasus

*

From the Oxford English Dictionary:

trepanation, n.

Pronunciation: /trɛpəˈneɪʃən/

Etymology: from trepan v.1 + -ation suffix; compare French trépanation (14th cent. in translation of Lanfranc).

The operation of trepanning; perforation of a bone, esp. of the skull, by a trepan.

c1400 Lanfranc's Cirurg. 126 — & þese, in as myche as touchinge trepanacioun, worchiþ best.

1598 A. M. tr. J. Guillemeau Frenche Chirurg. 56 b/2 — Opinione of Avicenna touchinge trepanatione.

1882 Athenæum 16 Dec. 817/2 — Numerous cases of surgical and posthumous trepanation.

|

* |

* |

* |

|---|

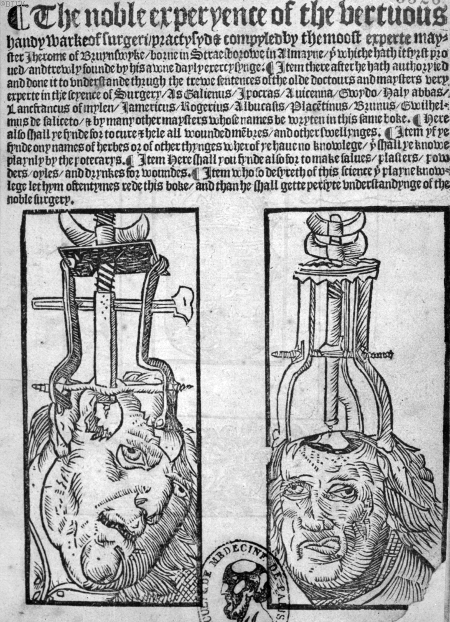

An engraving from the English translation of Hieronymous Brunschwig's Buch der cirurgia,

'imprynted at London in Southwarke by Petrus Treueris in the yere of our lorde god MDXXV'.

(The full title reads, perhaps rather optimistically considering the gruesome and hardly reassuring woodcut:

The noble experyence of the vertuous handy warke of surgeri, practysyd & compyled by the moost experte mayster Iherome of Bruynswyke, borne in Straesborowe in Almayne ... Item there after he hath authorysed and done it to vnderstande thrugh the trewe sentences of the olde doctours and maysters very experte in the scyence of surgery, as Galienus, Ipocras, Auicenna, Gwydo, Haly abbas, Lancfrancus of mylen, Iamericus, Rogerius, Albucasis, Place[n]tinus, Brunus, Gwilhelmus de saliceto, & by many other maysters whose names be wryten in this same boke. ... Item yf ye fynde ony names of herbes or of other thynges wherof ye haue no knowlege, yt shall ye knowe playnly by the potecarys. Item here shall you fynde also for to make salues, plasters, powders, oyles, and drynkes for woundes. Item who so desyreth of this science ye playne knowlege let hym oftentymes rede this boke, and than he shall gette perfyte vnderstandynge of the noble surgery.)

Adolf Dirr's obscure article on "Trepanation als gerichtlicher Beweis im Kaukasus" ("Trepanation as legal evidence in the Caucasus") was published in Wilhelm Kopper's (ed.) Festschrift / Publication d’hommage offerte au P.W. Schmidt: 76 sprachwissenschaftliche, ethnologische, religionswissenschaftliche, prähistorische und andere Studien / Recueil de 76 études de linguistique, d’ethnologie, de science religieuse, de préhistoire et autres (Wien: Mechitaristen-congregations-buchdruckerei, 1928; Wilhelm Schmidt, 1868-1954, was an Austrian Roman Catholic priest, philologist and ethnographer).

The article is extremely brief (perhaps unsurprisingly so), occupying barely a page and a half of the Festschrift's staggering 977(!) pages; I strongly suspect Dirr of simply having freely translated into German a small section of F.I. Leontovich's Russian-language Customs of the Caucasian highlanders (Odessa, 1883), to which Dirr refers about half-way through:

Es darf als bekannt vorausgesetzt werden, daß das alte Gewohnheitsrecht der kaukasischen Bergvölker genaue Vorschriften, besser gesagt, Tarife kannte, nach denen Verwundungen von dem Verursacher derselben gesühnt, d. h. durch materielle Leistungen wettgemacht werden mußten. Als Beispiele seien hier die Kopfwunden aufgeführt, und zwar die Entschädigungen, wie sie für solche bei den Juguschen, einem tschetschenischen Stamme, üblich waren.

Für eine Kopfwunde ohne Bloßlegung der Knochenteile wurde nur eine Versöhnungsbewirtung gefordert, ein Schaf und ein Kessel Branntwein. Ging die Wunde etwas tiefer, so daß etwa die Schädeldecke etwas abbekam und der einheimische Chirurg zur Reinigung der Wunde des Messers sich bedienen mußte, so kostete das bereits drei (trächtige) Kühe und zur Bewirtung einen Hammel und vier Kessel Schnaps. Wurde der Schädel so in Mitleidenschaft gezogen, daß die Wunde bis zur dura mater ging, so mußten sechs Kühe und zur Bewirtung ein großer Hammel und sechs Kessel Schnaps geleistet werden. Wurden aber beide Gehirnhäute (dura mater und pia mater) bis zur membrana arachnoida verletzt, so belief sich der Ersatz auf acht Kühe und Bewirtung wie beim vorigen Fall. Waren aber alle drei Schutzhäute des Hirns verletzt, so kostete das 16 Kühe und einen Ochsen nebst einem Stück Baumwollstoff im Werte von drei Rubeln; zur Bewirtung wurde ein großer und ein kleiner Hammel und sechs Kessel Branntwein gefordert. Damit war es aber noch nicht abgetan. Der Täter mußte dem Verletzten einen Arzt stellen und alle nötigen Arzneien bezahlen. Das Honorar des Doktors betrug gewöhnlich ein Schaf für jede Kuh, die der Täter dem Verwundeten zu bezahlen hatte.

Das Adatgericht, d. h. das Gericht, das nach dem Gebrauchsrecht, dem Adát Recht sprach, behandelte Körperverletzungen aber erst nach ihrer Heilung, also erst, wenn die möglichen Folgen einer Verwundung sich zu zeigen begannen. Bei größeren Wunden ließ man ein Jahr verstreichen, ehe das Gericht sich der Sache annahm.

Solche Folgen konnten aber auch erst später sich zeigen und da kam es häufig vor, daß solche Beschwerden -- die ja auch eine ganz andere Ursache haben konnten -- tatsächlich der betreffenden Verwundung zuzuschreiben seien. Man ließ dies nähmlich durch Trepanation feststellen. (Ich entnehme diese Daten einer außerhalb Rußlands wohl kaum auffindbaren Quelle: Леонтовичъ Ѳ.И., Адати Кавказскихъ горцевъ (Odessa 1883), Bd. II, p. 161 ff.) Wenn der Patient etwa Kopfweh bekam, meldete er dies seinen Verwandten mit der Bitte, sie möchten nach altem Brauch den Zustand seines Schädels feststellen. Dabei war es vollständig gleichgültig, wie viel Zeit zwischen der Verwundung und dem Auftreten der Beschwerden verflossen war. Es wurde also ein Tag für die Vornahme der Operation festgesetzt, bei der der damalige Täter, seine Verwandten, die Verwandten des Patienten und ein einheimischer Arzt zugegen sein mußten. Letzterer machte nun zunächst mit einem gewöhnlichen Messer einen Kreuzschnitt an der Stelle der ehemaligen Verwundung (diese Stelle bezeichnete häufig der Patient selber, ohne sonstige Beweise vorzubringen). Findet der Chirurg dunkle Stellen am Schädelknochen, so kratzt er sie mit demselben Messer aus und näht dann die Wunde zu. Nicht anders verfährt er, wenn sich wirklich schwere Verletzungen an der Schädeldecke zeigen. Ist Eiterbildung vorhanden, so schneidet der Arzt die eiternden Teile aus; gegebenen Falles saugt er den Eiter bis zum letzten kleinen Tröpfchen heraus.

Da die ganze Operation ohne alle die Hilfsmittel der modernen Chirurgie vorgenommen werden mußte, ging sie in vielen Fällen weit über die Kraft und die Widerstandsfähigkeiten des Patienten. Starb dieser, so war aber daran nicht er oder der Arzt schuld, sondern der ehemalige Täter wurde jetzt als schuldig erklärt und verfiel der Blutrache von seiten der Verwandten des Verstorbenen.

|

* |

* |

* |

|---|

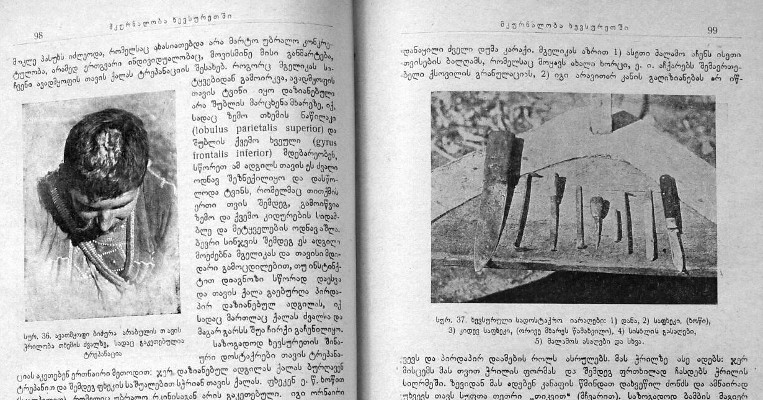

—A satisfied Pshav patient and the traditional tools of the trepanation trade—

from Dr Tedoradze's Five Years in Pshav-Khevsureti (Tbilisi: 1935)

|

* |

* |

* |

|---|

My free translation of Dirr's article:

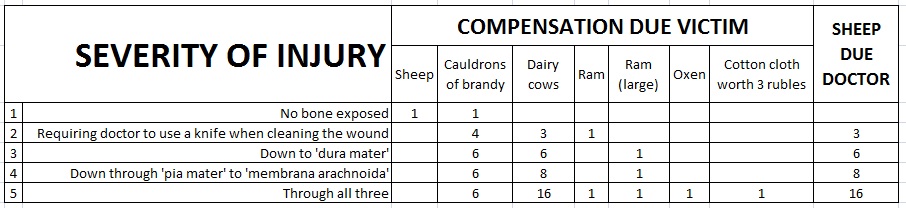

It is common knowledge that the old customary laws of the Caucasian highlanders included precise rules (or rather set out precise "tariffs") according to which parties guilty of having injured another were to materially compensate the latter. Using the example of head wounds, this article deals with the forms of compensation for such injuries which were current among the Ingush[*], a Chechen tribe.

Compensation for an injury to the head which did not expose any bone was limited to giving the injured party a sheep and a cauldron of brandy. If the wound went deeper, i.e. if there was damage to the skull requiring the local surgeon to use a knife when cleaning the wound, reparations due the victim immediately increased to three (dairy) cows as well as a ram and four cauldrons of brandy. If the wound was so deep it reached the dura mater, then the victim was owed compensation to the tune of six cows, a large ram and six cauldrons of brandy. If both cerebral membranes (dura mater and pia mater) were pierced down to the membrana arachnoida, then the guilty party had to pay eight cows, a large ram and six cauldrons of brandy. If all three membranes were injured, then compensation amounted to sixteen cows, an ox, a piece of cotton cloth worth at least three rubles, two rams (one large and one small) and six cauldrons of brandy. But this compensation did not settle matters entirely: the guilty party also had to provide the victim with a doctor and pay for the treatment, including all medical supplies and medicines. The doctor's fee was usually a sheep for every cow the guilty party owed the victim in compensation.

The adat court, i.e. the court which enforced adat according to customary law, would only consider injuries after they had healed, i.e. when their possible consequences had begun to reveal themselves. With more serious injuries, a year was allowed to pass before the court would consider the case.

The potential consequences of injuries to the head could, however, sometimes only reveal themselves at an even later date, and such ailments -- despite potentially resulting from a quite different injury or accident -- were often attributed to the case at hand. This was established by trepanation. (The source of my information is a work hardly to be found outside Russia: Леонтовичъ Ѳ.И., Адати Кавказскихъ горцевъ[*] (Odessa 1883), Vol. II, 9. 161 ff.) If the patient began to suffer from headaches, he would inform his relatives and ask for the condition of his skull to be medically examined in the old-fashioned way [nach altem Brauch]. In such cases the length of time which might have passed between the moment of the injury and the moment the victim officially accused someone of having committed it was considered irrelevant. A date for the procedure was set, to which the accused, relatives of his, relatives of the patient and a local doctor were summoned. Using a simple knife, the latter would make a cruciform incision through the scalp where the injury had been inflicted (this was often indicated by the patient himself, without him having to provide any kind of proof). If the surgeon discovered dark patches on the skull, then he would scratch them away with his knife before sewing up the scalp. If the patient's skull shows signs of him having sustained serious injury, the doctor proceeds in the same manner. Should pus be accumulating, he excises the purulent areas, sucking out every last little drop.

As operations such as these were necessarily carried out without any of the benefits of modern medical science, they would often demand greater strength and resistance than the patient could ever possibly possess. If he died, the surgeon, however, was absolved of all responsibility: the accused would instead be found guilty of the man's death, and would become the object of a blood feud with the dead man's relatives.

|

* |

* |

* |

|---|

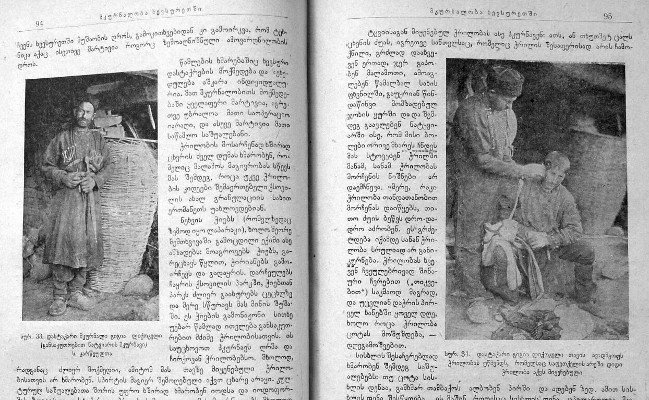

—'One sheep for every cow': a portrait of your local surgeon—

from Dr Tedoradze's Five Years in Pshav-Khevsureti (Tbilisi: 1935)

Unless stated otherwise or obviously not the case, all the text and images on this website are © A.J.T. Bainbridge 2006-2015

Do get in touch! Gmail: alexjtb