Dadaloba

The feast held for dadaloba in Tsovata in 2010

Dadaloba (Batsbur: დადალობა) is a pagan feast held every year in the meadows of Tsovata, the ancestral homeland of the Batsbi people. The Batsbi have long been bilingual in both Batsbur (a north Caucasian language related to Chechen and Ingush) and Georgian (a south Caucasian language completely unrelated to the first), and the word "dadaloba" comes from the Batsbur noun "dal", "God", to which the Georgian suffix "-oba", "the event of", has been added.

The Batsbi — originally, perhaps, an Ingush clan — lived in Tsovata (altitude: 2,200m) in the Georgian region of Tusheti for several centuries before migrating down to the less harsh and more fertile climes of Alvani (altitude: 600m) in the eastern Georgian province of Kakheti, due south. Their migration was final, the result of several landslides which almost completely destroyed two of their villages and of an outbreak of the plague, and since then the beautiful valleys of Tsovata have only been used as summer pastures for the many sheep which a few Batsbi still keep. The villages are in ruins, and in the square, roofless remains of the stone towers forests of nettles gently sway in the wind. The whole place is eerily beautiful.

* *

*

A panoramic photograph of Tsovata

(click for a larger view)

Head shepherd Petre Usharauli in front of his tents

The tent to the left provides shade for the cheese, which is made and kept in long plastic bags,

and the other is his home for the summer

Petre Usharauli's home-made mobile phone charger

Milking the ewes in wooden sheep folds — a tedious, back breaking and unenviable task

The ruins of the village of Indurta

*

* *

Every year in May, dozens of shepherds begin a long, arduous 3-week journey with their flocks from the winter pastures of Shiraki in eastern Georgia up through Kakheti and over the Greater Caucasus range to Tusheti and Tsovata. A handful of them stay in Tsovata during the summer months until early September, when the snows close the pass to Tusheti (altitude: 2,900m) until next May. They live in crude houses fashioned by stretching plastic tarpaulins over the ruins of their people's former towers, in former Soviet military tents, and in a few purpose-built wooden houses built in the 1970s and 1980s. These "head" shepherds employ others — mostly teenagers from Alvani — to help them with the hard work of watching over the sheep, shearing them for their wool, and milking the ewes in order to make guda, a traditional Tush cheese, heavily-salted in order to preserve it for the long winter months.

For more illustrations of the life of a Tush shepherd and his yearly transhumance between his flock's winter pastures on the Georgian-Azerbaijani border and the summer pastures of Tusheti, a series of photographs taken by Pierre Jeanmougin (link) comes highly recommended! In 2010, this young French photographer accompanied a "brigade" of Batsbur shepherds during their long trek from the plains up into the mountains.

All this hard, monotonous work in an isolated mountain valley leaves the shepherds and particularly the young men they employ desperate for any kind of entertainment, and the yearly dadaloba feast — with its exciting horse race, mountains of food, rivers of alcohol and many friends and guests — is eagerly-awaited by all.

The first to arrive for dadaloba are the three shultebi (Georgian: შულთა, "shulta", "host", plural "shultebi") i.e. the three men who were designated to host the feast by having their names drawn out of a hat (see the end of this post for more information).

The shultebi are responsible for organizing the feast. Each is expected to bring a third of the wine, bread, salt, vegetables, possibly fruit, &c. that the guests will require. In addition to this, each shulta must bring two sheep and sacrifice them to the shrine; these sheep provide the meat for the feast, and their pelts will be distributed to the riders who take part in the horse race. The shultebi are also responsible for bringing up a tablecloth and all the plastic cups, napkins and firewood necessary for preparing, cooking and serving the food. (Plates, dishes and heavy pots are kept in the shrine — perhaps for reasons more prosaic than religious.) Essentially, the shultebi are responsible for everything down to the smallest detail — the guests are merely expected to attend, to eat, and above all to drink.

A shulta supervises the cooking of the meat on a cold morning

A drunken guest has passed out by the fire

Dadaloba is held on the Sunday closest to the 1st of August, and can thus fall on the last Sunday of July or the first Sunday of August. On the day before, the sacred flags (Batsbur: ბერახ, "berakh") are taken out of the shrine and the celebrations begin. The bell which hangs inside the shrine is rung, and all shout "tskhalobde!" (Georgian: ცხალობდე!, "may the shrine grant you its power") and wish each other the power of the shrine (Georgian: ცხალობა ხატისა!, "tskhaloba khatisa!").

* *

*

The sacred flags are taken out of the shrine the day before,

and revellers drink to their exhibition

*

* *

Dadaloba

The day of the dadaloba itself begins at dawn the next day. The routine work of the shepherds continues as usual, but the first guests and the shultebi start heading up to the shrine at daybreak — the former to light candles and to bring offerings of chacha (twice-distilled grape brandy) or wine and kada (a sort of flat cake filled with sweetened clarified butter), and the latter to do the same and also to consecrate the sheep they have brought to the shrine. Only men are allowed up to the shrine. Most of them circumambulate the shrine three times in a counter-clockwise direction, sometimes making the sign of the Cross as they do so (this is almost certainly a Christian Orthodox or Georgian Christian Orthodox custom, as this circumambulation is quite common throughout Georgia, or it may predate Christianity), and small strips of white cloth are tied between the sacrificial sheep's horns as a sign of their having been consecrated. Any man may bring a sheep, and the task of doing so may be delegated i.e. one may bring the sheep of someone who could not attend.

The sheep are then sacrificed and skinned within low stone walls just below the shrine, next to the abandoned salude (Georgian: სალუდე, "brewery"). Two sheep, however, are placed in a saddlebag and one of the shultebi takes them to another shrine situated on the summit of the hill that rises above the abandoned village of Tsaro, some 10km away from Indurta. He is accompanied by another rider bearing one of the sacred flags and by all the young riders who will take part in the horse race later that morning. The horses and their riders will be blessed in Tsaro — an indispensible prerequisite to their participation.

* *

*

The sheep are skinned after having been sacrificed to the shrine near Indurta

Inside the shrine

The ruined village of Tsaro (the shrine is situated atop the hill)

One of the shultebi about to ride to Tsaro with the two sheep that are to be sacrificed there

The flag-bearer — an elder who is also responsible for ensuring that all the ceremonies are carried out properly

*

* *

The riders return from Tsaro more than an hour later, and their arrival is eagerly awaited. When they reach the lower end of the meadow which leads up to the shrine, below Indurta, the young riders who will take part in the race line up and await the signal to start. Most of the men watch the race from next to the shrine, for the winner will be the rider who reaches it first.

The men await the riders by the shrine

The riders suddenly leap forth and gallop up the meadow towards the shrine, approximately 1km away. It is possible that the race once started in Tsaro, as this distance seems rather short. (For more information on traditional horse races i.e. doghi, please see this page.) The first rider quickly reaches the low hill upon which the shrine has been built. Here he jumps off his horse, seizes it by the bridle or reins, and runs up the hill to the shrine. (This was described to me as the "proper" way of doing things. However, in 2010 the riders just galloped up the hill without dismounting.) The rider who touches the shrine first, wins.

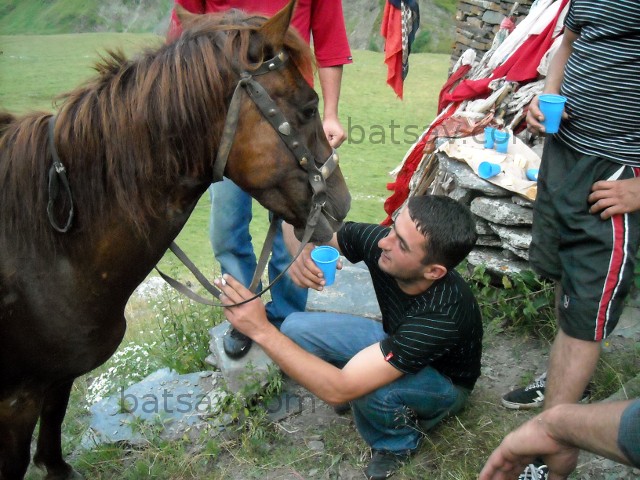

The winner of the 2008 doghi, Mirza Qizilashvili,

trying to get his horse to drink some chacha

The winner of the race drinks several toasts by the shrine, and he and the next two to arrive receive the skins of the sacrificed sheep as trophies. The winner is also allowed the signal honour of parading about with one of the sacred flags, which he must however replace(?) by the end of the day(?).

As soon as the race is over, the shultebi and the tamada they have designated invite all to seat themselves for the feast. The "table" is a length of plastic sheeting or paper rolled out in the grass between a narrow row of flat stones upon which the guests sit down. Placed on the table are plastic plates and cups, bread, cheese, salt, vegetables (tomatoes and cucumbers, and perhaps even fried aubergine slices, as in 2010, if the shultebi are somewhat less carnivorous than usual), and of course wine and chacha.

Note the rows of flat stones in the background, which will serve as benches

The toastmaster — who is equivalent to a "master of ceremonies" — proposes toasts to the shrine, to God, to Tsovata, to those who have gathered in Tsovata for dadaloba, to those who wanted to come but could not, to Georgia, to those who brought sacrifices and offerings to the shrine and lit candles and prayed, to those people who looked upon those who were making their way to Tsovata for dadaloba with kind eyes, to the shultebi, to the memory of the ancestors of the Batsbi, to the memory of those who built the towers, to the shepherds, to "the four-legged" i.e. to sheep, horses and dogs, to the guests, to the foreign guests, to women (who sit at the end of the "table" or, more often, nearby), to nature, to Tusheti, to Tush traditions, to those abroad, to the memory of "the great Tush" who taught the world about the Tush people and Tusheti, to the mountains, to children and to the future, to individual guests among those present, and so on and so forth.

All must drink and are expected to drain their glasses, which are constantly refilled. The men at the table who take it upon themselves to ensure that all their neighbours' glasses are kept full informally ensure that they have indeed drained them for the last toast, and chide or reprimand those who have not done so. Toasts to the memory of the deceased (called შესანდობარი, "shesandobari", in Georgian) are particularly important in this respect, and must be drunk standing up as a mark of respect. If many guests are present and the table is long, the tamada's toasts are relayed to the other end of the table by an assistant he has designated. (In 2007, roughly 40 people were in attendance — all of them men, and many of them young. In 2008, there were approximately 60 people seated at the "table", with a dozen women and children also present. In 2010, about 80 men sat down to eat, and 20-30 others (men, women and children) were seated nearby in tents.)

* *

*

*

* *

As soon as the long series of toasts begins, the shultebi and the young men who help them begin to bring the meat dishes from the pots which bubble away over fires nearby. The dishes are traditional fayre: kaurma (sheep's meat stewed in the sheep's own fat) and khashlama (pieces of boiled beef on the bone). Both are immensely fatty, and if one is lucky (as in 2010), pieces of meat grilled over embers on skewers are also served.

Traditionally, the women and girls would eat apart from the men. Alongside the long (30 metres) parallel rows of stones where the men sit is another, shorter pair of rows where the women apparently used to sit. Unlike the practice in many shrines — such as in Khevsureti or Pshavi — where the inhabitants from different villages (i.e. originally from different but related clans) each sat in their own designated place, I was told that in Tsovata the villages always sat together. This may be the case, but the fact that Batsbi men and women sat together on the same rows of stones in 2008 (but not in 2010, and this despite the traditional separation which exists between men and women in Tusheti and other mountainous regions of Georgia — men and women rarely, if ever, sitting at the same table or even eating at the same time) indicates that such a separation of the sexes is by no means known to or respected by all. Whether or not the women are "allowed" to join the men is probably up to a group decision.

The women and children seated at the end of the "table" in 2008

Also, as noted above, the women are not allowed to set foot upon the sacred hill upon which the shrine is built. Those women who wish to light a candle and pray instead go to a low "gate"-shaped shrine built of stones nearby which is apparently the "women's shrine".

* *

*

The women head to their own shrine situated in the field below the main (men's) shrine

(These photographs, taken in 2008, courtesy of Peggy Scremin)

*

* *

The toasts continue, and the feast drags on. And on and on. Some slowly leave, and the tamada retires when even he feels that he can no longer drink another drop of alcohol, but a hardcore of revellers stays on to drink, toast, and eat until the sun sets. When night falls, some begin to squabble over matters whose triviality alcohol has transformed into importance, and then even they are forced to slowly call it a day...

And thus dadaloba comes to an end in Tsovata, and all is peaceful except for drunken snoring and the barking of sheepdogs in the night.

* * * * *

Khinklaoba

The next day (Monday) is "khinkali day" (Georgian: ხინკლაობა, "khinklaoba"). Khinkali (Georgian: ხინკალი, boiled dumplings filled with sheep's meat) are prepared in the morning and are wolfed down with reheated food from the day before and washed down with more wine and grappa. (This tradition of eating fatty khinkali the day after the feast is certainly not only due to the need to finish the meat of the sacrificed sheep: Given the quantity of alcohol the men absorb during their stay in Tsovata, mornings are a little difficult...)

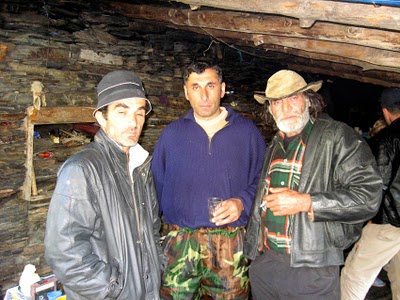

A traditional Batsbur breakfast scene

(a.k.a. "the three c's": chacha, cheese, and cigarettes)

Khinkali being boiled over a fire

The Batsbi (or some of them, at least) have a theory that the word "khinkali" (which is an isogloss in the Caucasus i.e. the word is the same in many unrelated languages viz. "khinkali" in Georgian, "khinkal" in Avar, "khingal" in Azerbaijani, &c.) actually comes from the Batsbur "khi" (water) and "[akl]" (the root of "to boil") i.e. "boiled in water". It seems quite possible — and "khi" is indeed the Nakh word for water — but many philologists would no doubt vehemently disagree with this theory. (Some of the most pig-headed Batsbur proponents of this theory also claim that the words dalai lama are obviously of Batsbur origin, as "dal" in Batsbur means "God" and "lam" means "mountain"...)

Every three years, the names of the shultebi i.e. those who will host dadaloba for the next three years (see above) are drawn from a hat while the khinkali are being prepared.

The names of the next nine shultebi are drawn from a hat in 2007

The draw is done for nine shultebi i.e. three per year for the next three years. They must be married men and must be Batsbur i.e. belong to one of the dozen or so Batsbur gvari (Georgian: გვარი, "clan", "extended family"). Given the prevalence of mixed marriages nowadays (i.e. between Batsbur and non-Batsbur couples), at the very least, their father must be or have been a batsav.

Having one's name drawn from those that were written down on small pieces of paper and placed in the hat is considered a signal honour, and many men dream of having their name drawn and of having the financial means to host a dadaloba (an expensive undertaking).

Young, unmarried men also put forward their names, and if theirs is chosen the honour is their father's (or in some cases possibly that of another married male relative). The names of those working and living abroad are also placed into the hat; if the name of such a person is drawn and he cannot return to Georgia in order to be a shulta, he can be moved to a later year by common agreement.

The draw seems to be completely individual and the number of participants does not seem to be limited to individual families i.e. several members of a same lineage may take part on equal terms.

The next draw will take place in 2013.

* * * * *

2011: Tragedy in Tsovata

The 2011 edition of dadaloba was marked by several momentous events viz. the re-opening of the road to Tsovata (from Jvarboseli) by a bulldozer and a state visit of the bishop of Alaverdi and his merry band of men (and women).

The two are quite likely linked: The road was re-opened by the government, who were able to finance this (long-overdue) task thanks to an unexpected grant of money. As it happens, the bishop of Alaverdi had planned to spend his summer driving around Tusheti, travelling from pagan shrine festival to pagan shrine festival with the aim of strengthening the Georgian Orthodox Church's presence in Tusheti and of restoring a measure of proper Georgian Orthodoxy into the beliefs and rituals of his Tush flock.

The bishop was accompanied by a dozen or so high- and low-ranking clerics (abbotts, friars, nuns, &c.) and several other hangers-on (notably a cameraman and a photographer, several lay women and girls, and an choir of church singers). Add another 10 drivers or so and 3 policemen as escort, and the group numbered about 30 all in all. They arrived on the morning of the second day (khinklaoba), their convoy of cars driving up across the valley and coming to a halt at the very foot of the holy mountain, just below the shrine.

The bishop and his followers immediately walked up to the larger of the two ruins below the shrine (perhaps formerly a room in which the valley elders would have met to discuss affairs, the other ruin being that of the shrine's salude i.e. a small stone building in which sacred beer would have been brewed for religious festivals in the olden days). A large wooden cross was unpacked and set in a concrete base on top of a low pile of slate. As the audience (which included local Batsbi) removed stones from the ruins of the sacred brewery with which to build a lectern, the bishop and the abbotts changed into their ceremonial robes and then proceeded to consecrate the ruins as a church.

The ceremony lasted several hours, and was attended by around 30-40 people including a dozen or so Batsbi. Those who merely disapproved of the bishop's visit, however, got a nasty shock when the two nuns who accompanied him decided to walk up the path which leads to the shrine, stopping just by the "entrance" of the new church-to-be. Angry, disapproving shouts of ქალებისთვის არ შეიძლება! ["It is forbidden for women!"] rang out repeatedly (women not being allowed to walk on the holy mountain upon whose flank the shrine stands), and some men walked up to the nuns in a vain attempt to get them to immediately walk down again. The ceremony of consecration went on, regardless.

The nuns were, it must be said, naturally very modestly dressed, but there can be no exceptions to a rule as basic as this: just as women are not allowed to walk in certain areas of a church, some reasoned, the same applies to mountain shrines all over the Caucasus. The affront, however, became a veritable scandal when other (less modestly-dressed) women and girls decided to join the nuns — including local i.e. Batsbi women, their legs bare below the hemline of their skirts. For most of the other women and girls who stayed below, busying themselves with the preparation of the khinkali, this was anathema. Some Batsbi men — "true" Orthodox believers who were honoured by the bishop's visit — even encouraged their wives to join them on the sacred hill.

The stage was set, the quasi-colonial trampling of ancient traditions obvious, and the mood turned decidedly sour. With the ceremony over and the food ready, all those who had taken part walked down and joined a pretty disgruntled group of revellers, seating themselves at the head of the twin lines of flat stones. Most of the food was being sent up to the bishop and his group (which included women, who are normally not allowed to join the men during the feast), and locals at the other end of the table were left without khinkali, salt, cheese or bread, having to content themselves with unsalted tomatoes and cucumbers. Some were shocked and scandalized by this clear failure on behalf of this year's shultebi [hosts — see above]. The sunglass-sporting bishop and his band of followers tucked in to their free meal, and made matters even worse when they brought out their own wine in large 5l bottles but failed to share it with all those seated at the feast. The supra split into two halves — an unheard-of event.

The tamada [toastmaster] officiated among the bishop and his followers, leaving the other "local" half to drink on their own, in an unstructured and unguided manner. The bishop's choir began to sing songs, and catcalls could be heard coming from the locals seated at the other end. Perhaps sensing that they had overstayed their welcome, and no doubt pleased that they had succeeded in officially consecrating a church in Tsovata, the bishop and his followers decided to leave. Just before driving off, however, they handed out a stack of Georgian Orthodox magazines and leaflets explaining how to be a good Georgian Orthodox believer to some young local girls, telling them to distribute them among the others. One of the nuns even thought that the Batsbi were Muslim.

* * * * *

If these scenes were indeed repeated all over Tusheti this summer, the bishop will no doubt have succeeded in restoring a measure of "proper" Georgian Orthodoxy to the beliefs and rituals of the Tush — both Chaghma and Batsbi — but he will certainly have done so at the expense of the Tush themselves. Unsure of their own beliefs and divided by the question of the Georgian Orthodox Church's presence in their valleys and by their shrines, the Tush have been split into three camps: those who wish to do away with the old and embrace "proper" Georgian Orthodoxy, those who wish to preserve the old and reject any official attempt to "correct" or replace their beliefs and rituals, and those (whose view the Author shares) who would have been pleased and indeed honoured to welcome the bishop and his followers as guests, but who disapproved of what turned out to be a very heavy-handed, patronizing and disrespectful visit.

If the divinity to whom the shrine was originally consecrated centuries ago really does exist, it must be furious.

Unless stated otherwise or obviously not the case, all the text and images on this website are © A.J.T. Bainbridge 2006-2011

Do get in touch! Gmail: alexjtb