Masks in the Caucasus

The following is a hodgepodge of bits and pieces of information on masks in the Caucasus, mostly copied from various websites.

North Caucasian mounted masked hunting society, note the raised Mauser pistol. The horned mask is found on both sides of the Great Caucasian mountains — one more example of a common Mountain (as opposed to Plains) culture.

[From Robert Chenciner's Daghestan — Tradition and Survival (1997). The photograph was first(?) published in E.N. Studenetskaya's Maski Narodov Severnogo Kavkaza (1980), whose work Chenciner acknowledges.]

According to calendar widely spread in many Eastern countries winter begins on 22nd of December and lasts until 22nd of March. In some Dagestani villages a day of winter’s middle — 5th of February — is celebrated. This holiday is especially interesting and impressive in Shaitli village, where it is called igbi. Shaitli is one of auls of smaller nation of Western Dagestan whick is known as Didoyans (self-name is “cezy”, meaning “eagles”).

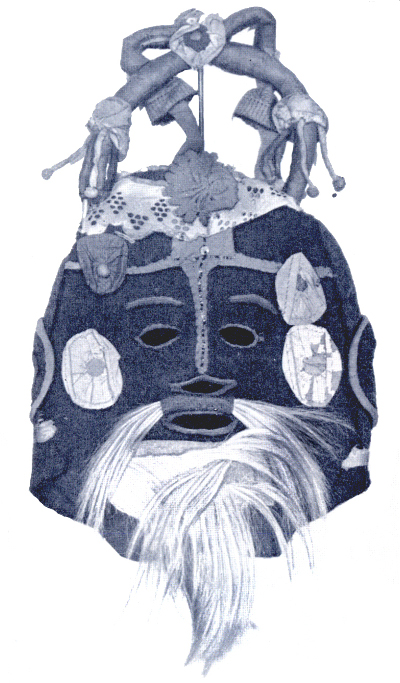

Main characters of igbi holiday are “wolves” who are played by youths dressed in special costumes and masks. The demonstrated mask is a part of a wolf costume (botsi). In many Eurasian peoples traditions wolf was not only the symbol of courage and valor but also a guard of spring crop growing. That’s why “wolves” are characters of igbi. It is considered that their appearance foretokens good harvest in coming year. During the celebration “wolves” “kill” mysterious creature Kvidili which comes down from the mountains on this day. This action is aimed at successful development of nature’s powers, as sources of Kvidili’s image are connected to idea of deity of vegetation.

Igbi holiday also goes back to tradition of men’s unions. This social institute was well known to nations of different continents, was important part of youth’s socialization and also had straight connections to ancient cults. People of Caucasus knew men’s unions too. igbi holiday, still celebrated by Shaitli dwellers, is one of last echoes of this ancient institute.

Scythians, ancient Germans and some other peoples had a belief that warriors – members of men’s unions could turn into wolves, and for that purpose they put on proper masks and imitated animals’ habits. Members of men’s unions at Caucasus also considered a wolf as their patron and supposed that they could turn into him. That’s where the wolf theme and symbols of igbi holiday comes from. The situation doesn’t change because of lack of botsi’s resemblance to wolf. The main thing is that both actors and spectators know who is who.

[From "Botsi: wolf mask from Dagestani settlement Shaitli" on this page of the website of the Russian Academy of Sciences "Peter the Great" Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography.]

Masks

Circassian aristocracy donned terrifying masks on their hunting expeditions, apparently to confound the prey, and together with the esoteric cant (щакIуэбзэ, schak’webze=language of the chase), render the objects of the hunt unaware of the true purpose of the chevy. According to E. N. Studenetskaya (1980), Kabardian princes, up until the first part of the 19th century, held secretive assemblies after the harvest that lasted for six weeks. In such assemblies, masks were used to hide identity so that the binding article in the code of chivalry on blood-revenge would not disrupt the smooth running of the martial exercises.

[From "Circassian Costumes & Accoutrements, by Amjad Jaimoukha" on this page of Circassian.com]

[Two photographs taken by the author on the outskirts of Tbilisi during the Georgian midwinter celebration called berikaoba. These masked young men stop passing cars and "hold up" their drivers and passengers for a few coins, a packet of cigarettes, &c.]

[From Letter IV of Prof. Kevin Tuite's "Letters home from Georgia".]

Dear friends & family,

Lent has now begun in Georgia. As in other Orthodox countries, one is not supposed to eat any animal product -- meat, eggs or dairy -- from now until Easter (23 April). The last week before Lent is called Cheese Week ("Qx'velieri" in Georgian), since this was the last chance to enjoy dairy products before the 7-week fast begins, and -- like Mardi Gras or Carnival in the Catholic world -- it is a period of feasting and festivals. My friend Mirian Xucishvili at the National Museum suggested we attend the Cheese Week festivities in the east Georgian village of P'at'ara Chailuri, where he had filmed the same festival 19 years earlier. According to the locals, carnival once lasted the entire week before Lent, until it was suppressed by the Soviet authorities. It was revived in the 1980's, but most events occur on the final weekend, to keep the children from skipping school.

1. Upon entering the village early Sunday morning, we were greeted by masked children brandishing whips. The masks are modelled after those worn by the main protagonists in the Carnival festival, known as Berik'aoba.

2. Regulation Berik'aoba masks are made of felt, feathers and strips of cloth, both some children made do with other materials, such as plastic flour sacks. The roll of cloth held by the child on the left will be rubbed in mud, to be smeared on the shoes, faces and car-windows of unfortunate passers-by.

3. Meanwhile, a team of seven young men and boys were putting on their costumes. Five of them are dressed as "berik'a", comical figures who in the course of the day will raid each household in the village, carrying off wine, bread and (live) chickens to be consumed at banquets later in the day. They are accompanied by a drummer and a boy dressed as a boar, shown above. The "boar" carries a dried pig-skin attached to a plank, to which is attached a jaw operated by strings.

4. Here are two of the Berikas just before beginning their rampage. Note the cloth mitten covered with mud.

5. Here is the Boar, wearing his distinctive contraption, and another Berika.

6. As the Berikas made their way through the village, raiding chicken-coops, smearing mud on cars and creating general mayhem, they were joined by masked children and others who joined in the fun. This group is blocking the main road through Chailuri, forcing drivers to pay money in order to be let through.

Some more random images (all from Daghestan) of Caucasian ritual masks gleaned from the internet:

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

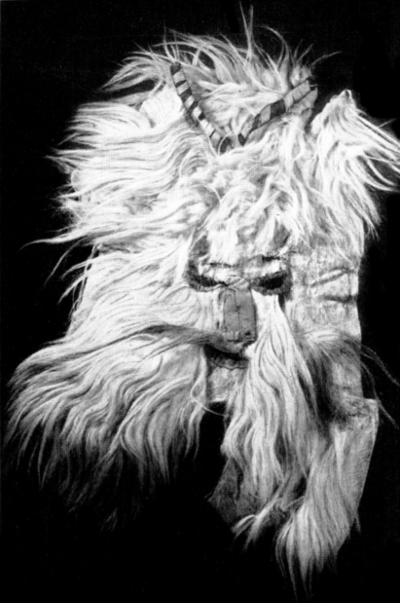

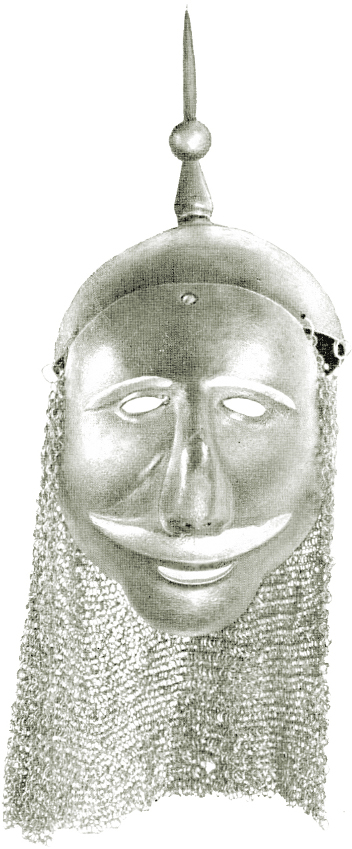

And two war-masks (also from Daghestan; both might actually also be ritual masks, and perhaps belonged to the "secret society of bachelors"):

|

|

|

|---|

Unless stated otherwise or obviously not the case, all the text and images on this website are © A.J.T. Bainbridge 2006-2011

Do get in touch! Gmail: alexjtb