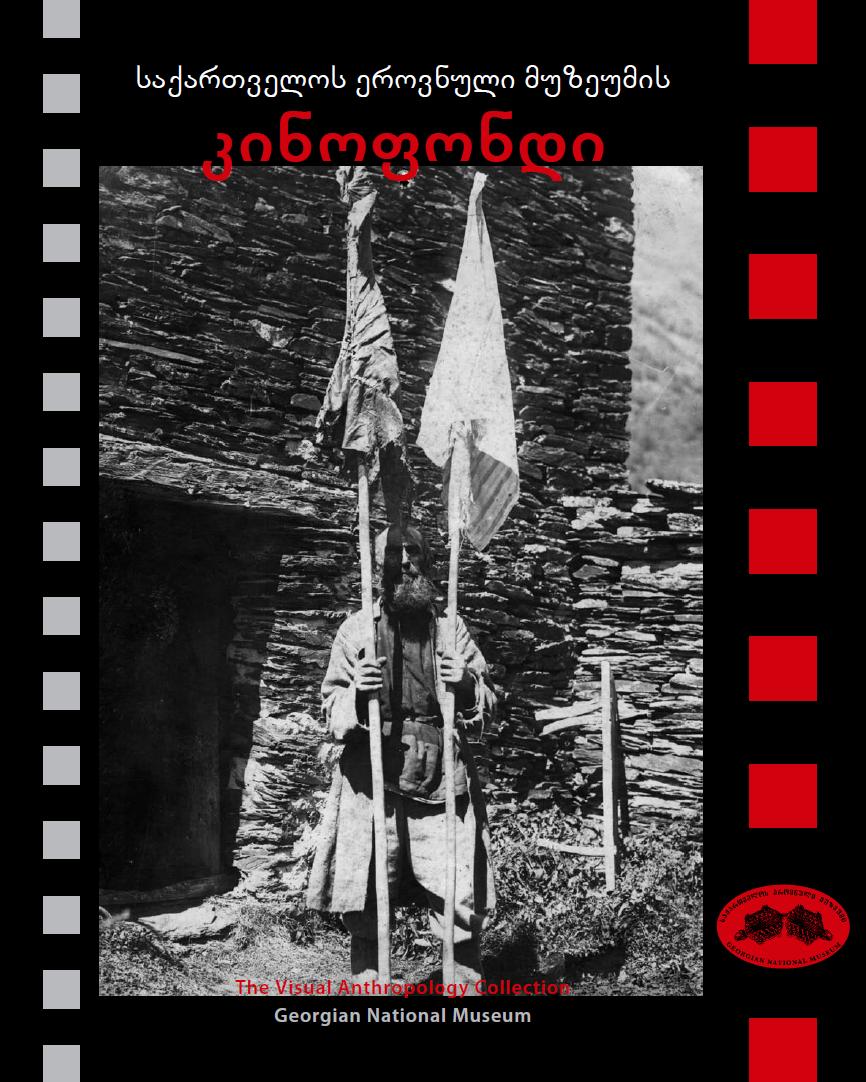

The Georgian National Museum's Visual Anthropology Collection

In 2005, UNESCO's Section for Museums and Cultural Objects began to support Georgia's National Museum in its efforts to preserve, restore, catalogue, and digitalize ethnographic films and photographs in its collections. A catalogue was published in 2006, and is available here.

The following introduction to the Georgian National Museum's ethnographic film and photograph collections was written by Prof. Kevin Tuite, Professor of Ethnolinguistics at the Department of Anthropology of the University of Montreal in Canada.

Prof. Tuite, a noted expert on the Caucasus and its peoples, took part in this project as a "UNESCO Expert".

The production, cataloguing and research-related use of ethnographic films in Georgia began in the sixties of the last century. The Department of Religious Studies of the State Museum was entrusted with this project, and as a result of the long-term activities of the department’s staff, a cinematographic and video collection was created at the museum. Film, video and photographic materials of great value are kept there. Mirian Khutsishvili (Cand. Historical Sciences) has directed the activities of the collection from the very beginning. As one of the founders of Georgian ethnographic film-making, for many years he has successfully employed his skills as both ethnographer and cameraman.

Ethnographic films have their own history: the idea of using documentary film as a historical source and as a means of conserving samples of cultural heritage was born together with the cinematographic medium. By means of film, researchers of cultural heritage were able to record and conserve materials of material and spiritual culture of people from archaic local zones. Subsequently video cameras and digital computer systems took their place alongside cinema and photography in scholarly research.

The first research expedition in Georgia to be equipped with cameras was organized by the staff of the Department of Religious Studies of the State Museum in collaboration with researchers from the institutes of archaeology and ethnography. In the course of these early expeditions in the highlands of Georgia, Georgian ethnographic documentary cinema was born. Although aspects of the spiritual and material culture and mode of life of Georgian highlanders had been filmed even earlier, these recordings lacked the main features of ethnographic films. In the latter, the scenes recorded are as natural as possible, without any script, or artificial props and scenery.

An ethnographic film made according to the above-mentioned standards is free from artificial visual effects. Under the guidance of consultant ethnographers, they are made according to the principals of visual anthropology. Professional directors while shooting ethnographic films often double as camera operators.

Since 1960 the national museum of Georgia has organized many expeditions in different regions of Georgia and throughout the Caucasus. They have filmed 300 hours of unique documentary material, showing not only the cultural heritage of Georgia, but that of Chechnia, Ingusheti, Kabardo-Balkaria and North Ossetia as well. It should be noted, that many aspects of the material and intellectual culture of these peoples, for different reasons, do not exist any more, and therefore their analysis is only possible thanks to the video materials conserved in the fund of the national museum.

Besides materials recorded by the museum staff, the collection contains old, rare tapes from former Soviet archives, showing the life and customs of the inhabitants of Georgia and some other parts of the Caucasus.

In a sense, the ethnographic films in the collection of the national museum are works of art, as attested by awards received at international festivals. This is particularly true of the following documentaries set in the highlands of Georgia: “Khevsureti”, “Tusheti”, “Pshavi”, “Mtiuleti-Gudamaqari”, “Tianeti”, “Along the route of the Transcaucasian Railway”, “Shrovetide in Georgia”, etc. In these films the traditional life of people is reflected documentarily. Among the elements shown are villages, sites of ancient settlement, fortification, homes. Special attention is paid to cultic sanctuaries and the traditional feasts and rituals connected with them, which are specific to the mountainous regions of Georgia. A large amount of raw footage that was not used in documentary films is classified chronologically and thematically and is kept in the video collection separately. Among this footage are scenes reflecting the spiritual and material culture of Svaneti, Racha and other regions of Georgia. Besides the ethnographic films in the fund, there is also an archive covering the history of the National Museum: scientific sessions held in the museum, conferences, anniversary celebrations of outstanding scholars. The collection also includes footage of archaeological expeditions, research projects and excavations carried out under the museum’s auspices.

The fund also contains some documentary and feature films obtained from the collections of museums that are no longer in existence, which may be of interest to historians and specialists in Soviet studies.

The materials in the ethnographic film collection of the national museum can be divided into several groups:

Ethnographic documentary films with added sound-tracks:

“Pshavi”, “Tusheti”, “Khevsureti”, “Mtiulet-Gudamaqari”, “Along the route of the Transcaucasian Railway”, “Shrovetide in Georgia”, “Georgians in Iran”, “Along the River Kura”, “Gelati”, “Georgian Museum”, “Gurian Riders of the Wild West”, “Racha-Lechkhumi”.

Raw film materials, without sound-tracks:

“Svaneti”, “Kakheti”, “Kartli”, “Tianeti”, “The Lashari Shrine of Tianeti”, “Samtskhe-Javakheti”, “Samegrelo”, “Abkhazeti”, “Saingilo”, “Dagestan”, “Chechen Ingusheti”, “Ossetia”, “Ingusheti”; also footage shot by the cameramen Sobol in Khevsureti and Svaneti.

Feature-length documentary films:

“Gurian Bandits”, “Before the Angels Come Back”.

Documentary-animated films:

“House of joy” , “A Toast to all who came”.

Video Films:

“Hard days of the State Museum” (a description of the museum in the early 1990’s);

Films describing archaeological excavations in Lagodekhi, Nokalakevi, Dmanisi, and Urbnisi.

Documentary films, raw materials, and feature-length films:

“Dimitri Shevardnadze”, “Gremi”, “Antiquities of Svaneti”, “The Painter Surmava”, “Georgia Boxing”, “Zari”, “Our Sergo”, “Peaceful Sky”, “The Siberian”, “Georgian Days in Erevan”, “Krazana”, “On the way of Friendship”, “Agriculture in Georgia”, “The Small Theatre”, “In the Family of Nations”, “Lesia Ukrainka”, “Opening of the Museum of Friendship”, “Soviet Georgia”, “Scholars’ Anniversary Celebrations”.

Many of the above mentioned films were inherited from the Museum of Friendship. Some of these films need urgent restoration and some are in critical condition.

As we mentioned above, most of the films were shot during research expeditions organized in various years. Despite the difficulties (often the films were made at 2800-3000 meters above sea level, in tough climatic conditions, using primitive cameras) the scientific expeditions were organized systematically and resulted in many hours of important, scientifically valuable material. Some of the earliest documentaries were filmed in the 1920’s-30’s, during the Soviet fight against the “survivals of religion” and “backward traditions”. Despite this, these films include unique pictures of the life of people in mountainous regions. The greater part of this material, before the fall of the Soviet Union, was kept in the Krasnogorsk central archives. Due to the efforts of the National Museum’s Visual Anthropology staff, it became possible to bring these early documentaries back to Georgia.

Since 1960, at the initiative of the Visual Anthropology staff, footage shot during research expeditions was used in the production of documentaries. Several films made on this basis were successful at various international festivals. Films produced by the museum received five main awards at the Pärnu (Estonia) International Documentary and Anthropology Film Festival during the years 1987-1991. Another film produced by the National Museum of Georgia was the winner at a competition sponsored by the American organization “Internews” in 2000. (In this feature-length documentary film the traditional life of people living in the mountainous regions is shown).

A major theme of the ethnographic footage in the National Museum archives is the traditional culture of the Georgian highlands, especially shrines and rituals. The choice of theme was in reaction to the rapid cultural change and loss of traditional practices undergone by highland Georgian communities. It could be said that visual documentation helped make it possible to preserve these traditional cultural features for study by future generations, since many of the material monuments and cultural practices, filmed during last 40 years, have since gone out of existence.

Of particular interest are highland religious cult monuments known to the local communities as “crosses” or “icons”, although in fact these terms designate both the divine beings worshipped in the highlands of the eastern Georgia, and the complex of shrines dedicated to them. At the annual religious feasts celebrated at these shrines, all members of the local clan strove to attend, although many of them lived in the lowlands. Some shrines had such great power that people from other regions of Georgia – and even representatives of non-Georgian tribes – came to pray and present offerings. In addition to shrines of regional significance, museum film-makers documented fertility shrines located near villages (“Place-Mother” or “Mother of God” shrines), and cultic edifices built on mountaintops, far from populated areas. Christian churches, monasteries, and festivals are also shown in the films. In some localities, evidence of syncretism between traditional and Orthodox Christian observances has been captured on film.

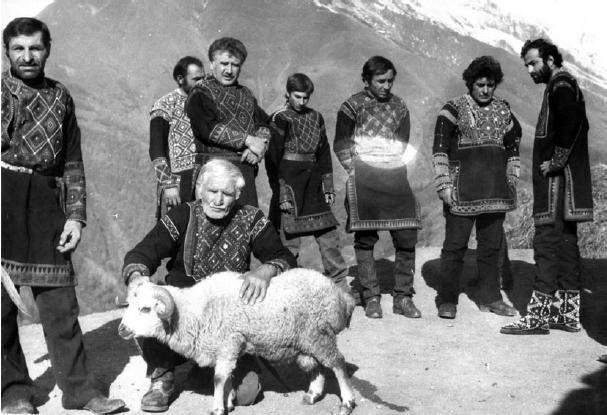

In addition to cultic monuments of different types and the rituals connected with them, film-makers also recorded scenes of traditional crafts, agriculture and practices of the highlanders (brewing beer, weaving carpets, horse-riding, weddings, fencing, mourning, etc.). Traditional costumes were also documented on film. Spectacular highland landscapes and monuments of material culture serve as background to scenes of the everyday life of local inhabitants and the problems they are facing – such as the continuous loss of population through migration to the lowlands – which pose a risk to the survival of the traditional life and culture of the Eastern Georgian mountaineers.

In conclusion, the ethnographic films and materials in the Visual Anthropology Collection of the Georgian State Museum are of considerable scientific importance and will be of great use to all experts and specialists, interested in the Georgian cultural heritage. This is especially true in view of the dramatic changes undergone by the traditional cultures of the Caucasus in the Soviet and post-Soviet periods. The study of many vanished elements of these cultures will necessitate reference to visual documentation kept in the museum’s collection.

The following is a list of films, as copied from the catalogue:

PSHAVI

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 120 min.

Author: Mirian Khutsishvili

1960–1979

The film opens with views of Magaroskari, the largest village and administrative centre of the present-day province of Pshavi. Scenes of the local school are shown, as well as demonstrations of traditional methods of rug-weaving and knitting socks. This is follwed by scenes of the village of Chargali, birthplace of the celebrated poet Vazha Pshavela, whose home has been turned into a museum. Rituals and merry making at a wedding party are shown, rich with the elements of traditional culture. After that film takes us up the Aragvi Valley to the historical territory of ancient Pshavi, beginning with the principal village Shuapkho. After the views of the village, cheesemaking and bread-baking are shown, followed by the feast of the Shuapkho community shrine. The shrines and sanctuaries of the eastern Georgian highlands are considered the earthly domains of the divine patrons of each community, and function as local religious centres. The shrine complexes of each Pshavi commune spread over a large territory, including edifices of various functions. This is where the annual mid-summer feast dedicated to the divine patron are held. Rituals are led by a traditional priest (Khevisberi) and his assistants (Dasturi). Each member of the community took part in the ritual.

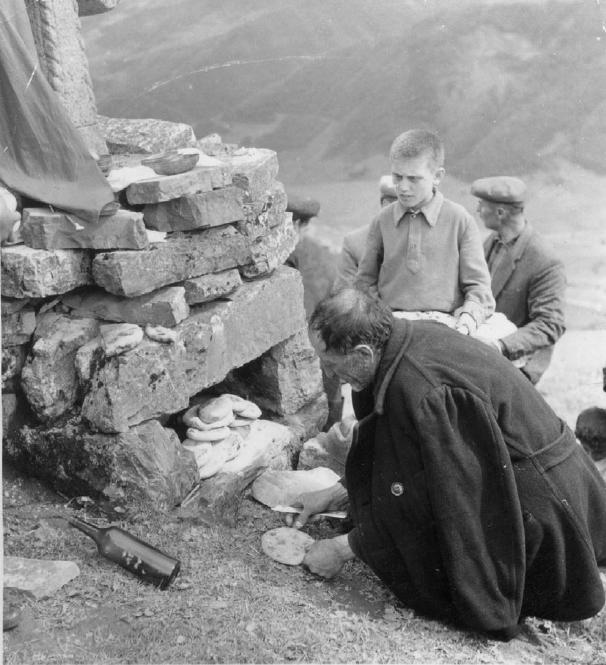

A number of shrines and festivals are shown in the film. The first takes place at the Iakhsar shrine on a mountain slope to the west of Shuapkho. Among the cultic edifices shown are Iakhsar’s sacrificial altar (a pit made of stones, where animals are slain by the Khevisberi); the place where offerings of various kinds of bread baked for the shrine are presented; the “beerhouse” where ritual beer was brewed in large copper vats; the tower where sacred banners are kept; the “candle-altar”; the highly-sacred tower known as “kvrivi”, marking the spot where the divine patron is believed to have touched the earth; and the treasury where silver and copper vessels belonging to the shrine are kept.

Next the film moves further upriver to the village of Gogolauri, that once was a community of 8 villages (the clans that inhabit Magaloskari and Chargali nowadays came from this territory). The Gogolauri St. George sanctuary complex is shown, which is located at two different places: the mountain shrine at Kmodis-Gori (at over 2000 meters altitude) and the abandoned settlement of Turmanauli. According to legend, the divine patron came down from Kmodis- Gori, drove away the residents of Turmanauli and settled there. The initiation ritual for newborn boys born to members of the clan, performed by the Khevisberi at St. George’s icon tower is shown. Also shown is the ancient granary with its distinctive pyramid-shaped roof, and the nearby bell-tower.

Not far from Gogolaurta is the village Muku, site of the shrine of the Virgin Mary. The complex includes a building for clan chiefs and a beer-brewing cabin built of slates (both structures are badly damaged). The beer-brewing implements are shown. Traditionally, the brewing process occurred five days before the religious festival. The beer was poured into large wooden vessels by dasturis (the priest’s assistants). The pilgrims would spend the previous night in the sanctuary and would attend the opening of the vessels. According to tradition, only after the beer vats had been opened and could the sacrificing of animals begin. When the sun reached the top of the mountain, candles would be lit, the beer was poured into cups, and first the clan chief and then the rest of the people would drink toasts to the glory of their patron sanctuaries. Afterwards bread offerings would be cut and the feast began.

The film records another religious monument, situated at the village Tchicho across the Aragvi River from Muku: the sanctuary dedicated to Queen Tamar (altitude 1780 m) and the badly damaged building where the dasturis once lived. Unlike the Khevisberi, who served for life, the dasturis performed their functions by turns, according to a certain order. During their term of service the dasturis were provided with food and drink by other members of the clan. The film also shows the bell-tower, an inscription on a copper bell, the place for cutting bread offerings.

The film includes scenes of the main sanctuary of all twelve clans of Pshavi – Lasharis Jvari. Lasharis Jvari, which is at quite a distance from the populated areas in the upper part of the river Aragvi, was the most significant public and religious centre not only for the people of Pshavi, but also for all Georgian highlanders. Moreover, it was closely connected to the lowlands in political, economic and, of course, religious terms. This is confirmed by the fact that Georgian kings and nobles gave generous donations and granted numerous estates to Lasharis Jvari in different parts of Georgia. Traditionally, Lasharis Jvari was also the centre for rendering justice – the specially gathered council of “counselor-chiefs” pronounced verdicts on religious issues as well as serious intra- clan disputes. Here were resolved the most urgent and important problems concerning the twelve clans of Pshavi – both internal and foreign affairs, including the issues of peace and war. According to tradition, the army of highlanders would never go to war without the blessing of Lasharis Jvari.

At the end of the film there are scenes of traditional ritual of “moving” the guardian angel of a household from an old to a new dwelling, conducted by the Khevisberi at the village Chinti.

TUSHETI

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 120 min.

Author: Mirian Khutsishvili

1984

The film begins at the village Alvani, followed by scenes showing shepherds’ everyday life (sheep-breeding was traditionally the most important economic activity in this region of the eastern Georgian highlands). There are scenes of grazing sheep in summer pastures. This is followed by views of the mountain village Omalo and the Tushetians’ dwellings, which represent quite interesting examples of folk architecture. A well-attended Festival of the Archangel was recorded at Omalo, including scenes of the brewing of ritual beer and components of the sanctuary: the candle-altar and a middle-sized stone tower (which the locals call “milionai”), believed to be the throne of the patron deity.

The commemorative banquet on the first anniversary of death and a mourning ritual were also shot at Omalo. The film includes scenes of wailing a deceased person, called dalaoba. Among the mourning practices in Tusheti, special importance is attached to the so called dalai, a commemorative horse-race conducted on the death anniversary. Five riders took part in the dalai: one – called the modalave – chanted verses in commemoration of the deceased while the other four sang an accompaniment. They laid out the deceased’s clothes in the yard, along with several pairs of socks, a tobacco pouch, rock-salt, roast barley, and wool poured milk into a bowl and began a loud wailing. The dalai riders mounted their own horses, whereas the modalave rode the horse in honour of the soul of the deceased, which was covered with black cloth and had a saddle bag over it. The rider of the “soul-horse” mourned aloud and sang in praise the deceased while the others sang the second voice. During pauses they were offered beer, part of which was spilt on the mane of the deceased’s horse and the rest was drunk in memory of the deceased.

The following scenes of the film present the village of Shenako. It shows residential and household structures, as well as the village’s Christian church. Then follow scenes of hay-mowing and rug-weaving, and religious festival at the nearby village Diklo, where a dry-built stone “milionai” is situated. A very interesting ritual is recorded in the village Kumelauri: after the festival drunk riders heading for the village are blocked by women armed with long sticks who try to throw them off their horses. Indeed everything is veiled with humour, but, apparently, this a bit strange habit must be related to some event that occurred in the past or a ritual that has been forgotten by now.

MTIULETI-GUDAMAQARI

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 30 min.

Author: Mirian Khutsishvili

1978

The film shows landscapes from the eastern Georgian districts of Mtiuleti and Gudamaqari, churches of St. George in the villages of Gogonauri and Chokhi, also local religious festivals and holidays.

The film begins with scenes along the Georgian Military Highway, alternating with typical images of local dwellers and scenes reflecting their household activities. A sanctuary at Gogniauri, situated at the altitude of 1500 metres, and a sacrifice ritual are shown. It is followed by St. George’s church at the village of Mleta and a crowded festival. Then we move to the Lomisis Jvari sanctuary, located not far from an early Christian period basilica.

The film goes on to show the church at the village of Chokhi and scenes of the economic life of the villagers. In Gudamaqari the festival dedicated to the Pirimze piris angel’s icon is shown (the icon was brought from Khevsureti and pilgrims from there also participate in the festival). The film-maker also recorded the sacrifice ritual conducted by the clan priest.

At the end of the film there is a modern festival dedicated to the “Shepherd’s Day” at the village of Tsivtsqaro, in the district of Dusheti, which includes a wrestling tournament and a concert of folk groups.

KHEVSURETI

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 80 min.

Author: Mirian Khutsishvili

1995

The film mainly uses archival footage shot in the 1920s by the cameraman Sobol. It shows scenes of the Khevsurs’ everyday life (haircutting, shaving), portraits of Khevsur women and men and their activities: weaving rugs, sewing, mowing, forging daggers, making cheese and so on. It shows traditional Khevsur men’s and women’s costumes. It records the ritual celebrated on the fortieth day after death: going to the sanctuary, decorating the horse of the dead, plaiting the horse’s tail, the feast held in the name of the dead. There appear buildings of the sanctuary at the village Gudani, the treasury (objects donated to the sanctuary), also the ritual of a child’s consecration to the sanctuary, or “blood-baptism”, after which he/she was regarded as the “vassal” of the sanctuary for life. There follow scenes of sacrificing domestic animals to the sanctuary, also the ritual horse-race with dozens of riders. Afterwards there occurs the ritual of “decorating the flag” by the traditional priest. Small bells hanging on the flag were the necessary attributes of the flag. The bell was conceived by Georgian highlanders as an instrument of God’s Revelation as well as a means for driving evil spirits away, that is why the bells were rung whenever the flag was used in the ritual.

There follow scenes of the Khevsurs’ economic and everyday life – crossing the river on horses, forging a horseshoe, greeting rituals, traditional swordplay, ploughing, sowing and so on. There are scenes of villages from Northern Khevsureti (Arkhoti, Mutso, Shatili), residential and agricultural buildings.

The custom of sacrificing a horse to the deceased is related to once-widespread beliefs about the afterlife among the East-Georgian highlanders. Such a horse was called a “soulhorse”. During the mourning ceremony it would be washed, its mane would be plaited, a velvet pad decorated with beads and buttons was attached to the mane, the tail would be plaited and pieces of coloured cloth would be tied to it. Then the horse was saddled, a lit candle was fixed to the saddle seat and a whip was hung on it. A saddle bag with bread and vodka was put over the saddle and the decorated horse stood by the deceased’s corpse on the funeral day. The “soul-horse” played an important role in the ritual horse-race (“doghi”) arranged on the first anniversary of death, which is also recorded in the film. The horse was again ornamented as described above, and put in front of the race riders (it did not take part in the race itself).

The race was an indivisible component of the ritual of commemorating the dead and was considered a sign of great respect. As a rule it was held on the death anniversary (there were some exceptional cases when the race was held on the funeral day). At least five riders took part in the race, although the more horses participated in the race, the more respect it showed to the deceased and his/her family. The race was held on behalf of dead people of either sex.

Special care was taken to prepare racing horses: the tail and the mane were plaited and decorated with coloured beads. The race horses were never saddled (only the “soul-horse” was saddled): there was only a band round the horse’s for the riders to hold on to. The winner was presented with awards by the mourners: livestock, rugs, and sometimes money. The race was attended by the whole village, and the riders were welcomed and taken to a special place where they drank toasts in honour of the dead.

The film shows traditional everyday life and activities of mountain Khevsurian villages, abundantly permeated with archaic elements. Original clothing, habits and customs, residential and housekeeping constructions are recorded. There is special focus on the unique medieval residential complex at the village Shatili.

SHROVETIDE IN GEORGIA

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 30 min.

Author: Mirian Khutsishvili

1986-1988

The film shows an ancient Georgian festival as celebrated at the villages of Ude, Vale, Patara Chailuri (Sagarejo district) and Matani (Akhmeta district). The Georgian Shrovetide festival was usually held in the early spring, during the week preceding Christian Lent (known as “Cheese Week” in Georgian). Shrovetide is of pagan origin. However, it was not repressed by the church and was incorporated into the Easter cycle of the Orthodox calendar. A carnivallike festival called berikaoba or qeenoba takes place in Shrovetide week throughout Georgia. A ritual was carried out on each day of the week, intended to see winter off and welcome a new farming year. While a number of folk festivals have forever been forgotten, berikaobaqeenoba has survived in Georgian custom for a long time, doubtless due to its popular theatrical nature. The film shows how modern life merges organically with traditional cultural elements – how the participants of the festival try to accommodate archaic customs with modernity, in keeping with the reality of their lives.

ALONG THE ROUTE OF THE

TRANSCAUCASIAN RAILWAY

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 120 min.

Author: Mirian Khutsishvili

1985-1991

In the late 1970s plans were announced to construct a gigantic 25km-long railway tunnel through the Caucasus, which would have shortened the main line between Georgia and the Russian Soviet Federation by several thousand kilometres. The grandiose scale of the project and the dangers it posed caused an extremely negative reaction among the society, which eventually prevented the project from being accomplished. Numerous cultural-historic monuments along the route of the proposed Trans-Caucasian main railway were put at risk of damage and destruction; according to independent experts, flora and fauna were also facing significant ecological danger. It is noteworthy that the events brought about by the Trans-Caucasian railway project played a very important role in the process of intensifying national consciousness – the already weakened Soviet regime was made to retreat and acknowledge public opinion, which was not at all characteristic of the establishment. It is not accidental that several years later the Soviet empire disintegrated.

The main task of the authors of the film was to record those cultural-historic monuments located along the route of the projected Trans- Caucasian railway system. Despite the existing censure limitations the film shows the heterogeneous attitude of the society towards the building process as it was underway.

The film begins with views of the village of Ksani and its medieval castle. They are followed by scenes of archaeological excavations at Ksani and Dzalisi, which were financed from the funds of the Trans-Caucasian railway project (in this sense the unaccomplished building project had great importance – it became possible to excavate a number of interesting archaeological sites through the project’s budget). An interview with the head of the archaeological expedition is recorded, followed by a tour of the important historic sites that were revealed as a result of excavations, for example, the Classical period cemetery and the 2nd century Romantype mosaic bath floor with images of Dionysus and Ariadne. The film shows the visit of the president of the Georgian Academy of Sciences and of Georgian academicians to the site and their discussion on the importance of the newly- discovered cultural-historic monuments.

The next section through which the railway line was to pass is the village of Tsilkani. The early-medieval basilica-type church and a festival dedicated to St. George – the most popular Christian saint in Georgia –are shown. Next there are scenes of village of Saguramo, and the house-museum of the prominent 19th century Georgian public and literary figure Ilia Chavchavadze. This is followed by scenes of the Georgian Orthodox Patriarch’s visit to the Zedazeni monastic complex near Saguramo, after which are shown various monuments along the building site of the main line: Chadijvari church, Bodorna, Aranisi, the village Zhinvali and the Zhinvali power station and reservoir. The film then moves further up the Aragvi Valley to the village Chargali with the house-museum of another popular 19th century Georgian writer, Vazha-Pshavela. It is followed by views of mountainous regions of Pshavi, the village of Shuapkho and the Iakhsar clan sanctuary. In the Khevsurian village of Korsha the ceremony of wailing over the deceased and the horse-race in commemoration of the dead are shown. There follows footage of a clan sanctuary in the village Vakisopeli and the associated religious festival. It is followed by the scenes reflecting shepherds’ life, sheep-shearing, cheese-making, etc.

Work carried out to build the tunnel, with the use of heavy machinery, dynamite, etc., is observed in passing.

In the second half of the film are shown various Khevsurian villages, as well as construction work along the Arkhoti Tarsk-Orjonikidze segment of the Trans-Caucasian railway route. The film includes a communal ritual at the shrine of Arkhoti in northern Khevsureti.

At this point the scene shifts to the North Caucasus, and to Ingushetian territory. The Assa Valley is shown, where work was then underway on the northern entrance of the railway tunnel. This is followed by scenes from the Ingush village of Targim, with its residential towers – monuments of traditional Ingush architecture –, the fortresses of Egi-Kale and Vovnushk, and the 11th century Christian church Tqoba-Erda, where Georgian inscriptions and bas-reliefs are to be seen. Also shown are archaeological excavations underway at the site of the Egi-Kale fortress and a local cemetery.

Also recorded on film is the Ingush village of Erzan, with scenes of its towers, local residents and their agricultural activities. A local beekeeper is shown, who says his ancestors came from Georgia several centuries earlier.

The final segment of the film begins in the villages of Jeirakh and Tarsk. Local residents are shown, along with their traditional costumes, mourning and burial rituals, and also scenes from a wedding celebration. Of particular interest is the Miatlom shrine built atop the 2500- meter Mt. Stalovaya. The film ends in Orjonikidze (now renamed Vladikavkaz), the capital of the North Ossetian Republic. A Georgian-language school that existed at the time of the film is shown, along with a church and other noteworthy sights.

SVANETI

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 70 min.

Author: Mirian Khutsishvili

1960-1990

The Museum’s collection includes footage of the high-mountain province of Svaneti shot by the museum staff along with that recorded by the cameraman Sobol in the 1940’s. The film depicts the traditional culture of the Svans and elements of their daily life: agricultural activities such as hay-mowing, threshing, forestry, vodka distilling, traditional clothing, round-dancing, and sporting activities such as stone-lifting competitions.

Also shown are aspects of contemporary life in Svaneti: the school, kindergarten, and medical clinic in the principal village of Mestia, also the local museum, with its rich and unique collection of artefacts from the region. Ushguli, one of the highest settlements in Europe, is also featured in the film.

Since the 1920’s, Svaneti has attracted tourists and mountain-climbers. An international mountaineering camp was established at the village of Ailama, from where expeditions set out each year to conquer the high peaks of Ushba, Shkhara and other mountains. A team of mountain- climbers is shown in the film as they prepare for an ascent of Mt. Shkhara.

THE LASHARI SHRINE OF TIANETI

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 80 min.

Author: Mirian Khutsishvili

1988-1990

The deity known as Lashari is one of the most powerful figures of traditional East-Georgian highland religion. Besides Lasharis Jvari, the main shrine of Pshavi, sanctuaries bearing his name are found in Tusheti and Tianeti. This last-named shrine is featured in this film, recorded by members of the visual anthropology team of the Georgian State Museum.

The existence of shrines to Lashari in Tusheti and Tianeti is association with a tradition, according to which those inhabitants of the East-Georgian highland who refused to accept Christianity resettled in these areas, setting up shrines to their chief divinities. It is a noteworthy fact that those who participate in the festival of the Lashari Shrine of Tianeti regard themselves as descendants of Pshav mountaineers.

The film contains scenes from the popular festival of the Lashari Shrine, including breadbaking, animal sacrifice, and the presentation of bread-offerings to be blessed by the Khevisberi (traditional priest).

TIANETI

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 80 min.

(raw film material)

Author: Mirian Khutsishvili

1988-1990

This footage includes scenes of the procession of the Khevisberi (traditional priest) and several dozen worshippers from Akhmeta to the Lasharis Jvari shrine of Tianeti. In earlier times, Lasharis Jvari possessed so-called “shrine lands” near Akhmeta – traditionally, such lands included farmland, hayfields and pastures, which were situated at a considerable distance from the shrine itself. The worshippers, lead by men bearing Lashari’s banners, begin with prayers at a small shrine near Akhmeta, and along their route they stop at other holy sites, where they are met by local people bearing food. Most of the residents of these villages are of Pshavian origin, and consider themselves “vassals” of Lasharis Jvari. Toward the end of the route, the procession stops at the shrine of Queen Tamar at Tamar Ghele, where they spend the night. The next day they proceed to the Lasharis Jvari shrine of Tianeti, where the annual festival takes place.

Besides the above, the film also contains scenes of the feast of the Dormition of Mary, and the remarkable medieval church located near the village of Kvetera, one of the jewels of Georgian architecture, at the seat of an ancient principality. Also shown are the medieval basilica at Zhaleti, and various aspects of daily life: wood-cutting and transport downhill, butterchurning, knitting, etc.

KAKHETI

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 50 min.

(raw film material)

Author: Mirian Khutsishvili

1960-2001

This film features the Christmas ceremony at Nekresi Monastery in the eastern province of Kakheti. This is the most important Christian holiday at this monastery, and every year a large number of people turn up. Parents and their children come to attend the ceremony, and spend the preceding night in tents. Nekresi is the only Orthodox Church in Georgia where people bring pigs to be sacrificed. Various stages of the ceremony are shown: sacrifice, praying and feasting.

The remainder of the film depicts the daily life of the residents of Lapaskuri, a Kakhetian village inhabited by people resettled from the mountain district of Pshavi. They have not abandoned their traditions. In the village there is a shrine brought from the highlands, where the annual shrine festival (“khatoba”) is celebrated. Scenes are shown of the festival, the baking of “kada” (a type of bread with a sweet filling), cow-milking, the blacksmith, etc. Also shown is a special wish-tree called “sakadrisebiani”, on the branches of which community members tie strips of cloth while imploring the shrine to fulfill their wishes. The film concludes with images of the memorial and obelisk erected in honour of local soldiers killed in World War II.

KARTLI

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 30 min.

(raw film material)

Author: Mirian Khutsishvili

1965-1995

The film begins with scenes of the “Giorgoba” (St. George’s day) festival at the church of St. George at Geri near Gori. A procession of cars and canvas-covered carts are shown moving towards the church, as well as scenes of worshippers circumambulating the church on their knees. It was earlier believed that Geri St. George aided people with mental afflictions. Such individuals were tied a tree overlooking a deep gorge near the church – a form of “shock therapy” that occasional produced positive results.

Next the film presents the feast of the Virgin Mary as celebrated at Kvatakhevi Monastery. This is the second most popular Christian festival in Georgia after Giorgoba. It is followed by the Didgori Festival at the local church of St. George. The film shows a ritual performed on behalf of small children: a woman circles three times around the church on her knees, carrying a child in her arms, while rolling a ball of white thread in front of her. The film also shows the landscape and lifestyle of the local community.

KHEVSURETI AND SVANETI

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 30 min.

(raw film material)

Footage shot by the cameraman Fivel Sobol

1940-1960

The Novosibirsk film-maker Sobol recorded ethnographic footage in the highland provinces of Svaneti and Khevsureti. This film was brought to Georgia and added to the Museum’s archive at the initiative of M. Khutsishvili.

The footage from Khevsureti consists principally in scenes of the landscape, the local people, and their traditional costumes. Also shown are scenes of traditional swordsmanship – a highly-developed art in Khevsureti –, processions of banner-bearing shrine personnel, horse-riding, etc. This section concludes with views of the village of Shatili, children’s costumes, and other aspects of daily life.

The footage from Svaneti comprises many scenes of the landscape and the high peaks of the Caucasus. The village of Mestia and its residents are shown, as well as their houses and medieval defence towers. This is followed by scene of a funeral, mourning and burial. The traditional technology of collecting gold from the river is shown, which according to some scholars may be at the origin of the legend of the Golden Fleece.

RACHA-LECHKHUMI

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 35 min.

(raw film material)

Author: Mirian Khutsishvili

1965-1980

The film begins with landscape views of Racha, another of Georgia’s highland provinces. The town of Oni, administrative centre of Upper Racha, is shown, including scenes of its old neighbourhoods. From medieval times until their recent migration to Israel, Oni was home to a thriving Jewish community. The synagogue is shown, with its ancient manuscript Torah, one of the oldest known, which is brought out on holy days. The architecture of the synagogue is shown. Some centuries ago, the present building was erected on the foundation of an older edifice.

The film continues with scenes further up the Rioni Valley, including the village of Shkmeri, with its residents and traditional houses. This is followed by scenes of Ghebi, a village near the frontier with Svaneti, with its distinctive domestic architecture; then come scenes of the near-by towns of Chiora and Glola.

There follows a depiction of the 9th-century St. George Church in the village of Mravaldzargva, one of the oldest churches in the region. Scenes of the festival of the Dormition of Mary are shown, which is attended by worshippers from all parts of western Georgia. The film concludes with the official opening of a hospital in Oni, which took place in 1975.

SAMTSKHE-JAVAKHETI

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 50 min.

(raw film material)

Author: Mirian Khutsishvili

1969-1998

This footage was shot in the southern province of Samtskhe-Javakheti. The film begins at one of medieval Georgia’s most extraordinary achievements, the 12th-13th century monastery complex of Vardzia, which is built into the wall of a cliff overlooking the Kura (Mtkvari) River. This royal monastery, dedicated during the reign of Queen Tamar in 1185, has played an important role in Georgian history. Featured in the film are the Cathedral of the Dormition of Mary, built in a large chamber cut out from the cliff face, with its splendid wall paintings (including portraits of Queen Tamar and her father Giorgi III); various rooms, monastic cells and defence structures from the 13-story complex; a two-story bell tower adorned with elaborate stone carvings, erected after the earthquake of 1283, which caused serious damage to the monastery; and other noteworthy structures. The complex once contained living quarters for 120, and 420 rooms, including 25 wine-cellars with 185 large wine-jugs buried in the floor. There were also at least a dozen chapels, many of them adorned with wall paintings. Most of the icons and other precious items kept at Vardzia were carried away by an invading Persian army in 1551.

After Vardzia, the film crew recorded views of Apnia, a village at 1700 m altitude on the Akhalkalaki Plateau overlooking the right bank of the Kura, and its early-Christian period basilica and bell-tower. This is followed by the ruins of a 10thc. church at Kumurdo, in which ancient inscriptions are preserved, including the name of the architect (Sakotar) who was commissioned to erect the cathedral. Then the film moves to Sapara, site of an important monastery complex, including the Church of the Dormition (10thc.), the Church of St. Saba (c. 1300), the belltower and castle. (At the time, Sapara was the residence of the Jaqeli princes, who ruled over Samtskhe-Javakheti). Next shown is the 8th-9th c. monastery complex at Zarzma, with its church, bell-tower, refectory and other buildings.

The next section of the film is set in the villages of Khizambavra and Saro, settled by members of Georgia’s Catholic minority. Due to long-standing contacts with the Roman papacy, Catholic missionaries came to Georgia at various times, some as early as the 13th century. A Catholic bishopric was founded in Tbilisi at the order of Pope John XXII in 1329. The influence of the papacy declined in the face of Turkish expansion, but resumed in the early 17th century with the arrival of Italian missionaries, some of whom left detailed accounts of life in Georgia at the time. Georgian Catholic communities are primarily found in the cities of Tbilisi, Gori and Kutaisi, and especially in the southwestern districts of Akhaltsikhe, Samtskhe, Artaani and Shavsheti.

The film concludes with scenes of a basilica in the village Zeveli, and a memorial in Saro erected to commemorate local soldiers killed in World War II.

ABKHAZIA

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 10 min.

(raw film material)

Author: Mirian Khutsishvili

1971-1980

This brief film features scenes of the St. George festival (“Giorgoba”) at the 11th-c. church of St. George at Ilori, which takes place every year on 20 November. According to tradition, and 17th-18th-c. documents, it was believed that a bull would miraculously appear inside the Ilori cathedral during the night preceding Giorgoba, which would then be sacrificed at the festival. Portions of the slaughtered bull’s meat were kept by the worshippers, who believed it warded off evil and illness.

OSSETIA

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 10 min.

(raw film material)

Author: Mirian Khutsishvili

1975

This footage was recorded in the North Ossetian village of Dargavs, the site of an ancient cemetery or “city of the dead”, with its mausoleums, gravestones, etc.

DAGESTAN

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 40 min.

(raw film material)

Author: Mirian Khutsishvili

1960-1985

This footage includes views of the impressive scenery of Dagestan, beginning with the villages Gunib and Upper and Lower Kuban. The distinctive layout of Dagestan villages is shown. The gold- and silversmiths of the village Kubachi are renowned for their artistry throughout the Caucasus. Examples of their daggers, swords and other pieces of craftsmanship are shown. Evidence of former Georgian cultural influence in Dagestan is shown in the form of a church with Georgian inscriptions.

Also shown are the citadel of Narinkala in Derbent, and also the site in Gunib where the Imam Shamil surrendered to the Russian General Bariatinsky, ending the decades-long resistance of the North Caucasian tribes, at least temporarily...

The film concludes with views of the narrow streets, houses and wood-carved balconies of Gunib, and a cemetery in Derbent.

SAINGILO

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 10 min.

(raw film material)

Author: Mirian Khutsishvili

1975

The formerly Georgian province of Saingilo is now part of the Azerbaijan Republic. The local population still retains the Georgian language and many of their former traditions, despite being surrounded by a Muslim majority. They also have a Georgian-language school and theatre. The film shows the Church of St. George at Kurmuxi, and the people praying there.

GEORGIANS IN IRAN

B&W. 35 mm. Approx. 20 min.

Author: Irakli Kandelaki

1944

This film shows the everyday life of the Georgian community in Fereidan, Iran. It also describes the history of 200 000 Georgians exiled by Shah Abbas I in 1614-17. These people were settled in Fereidan where they established several Georgian villages. Although they were compelled to change their religion, they have preserved the Georgian language and many ancestral traditions.

GURIAN BANDITS

Documentary film. DVD. Approx. 23 min.

Author: Irakli Makharadze

1999

The film depicts the adventures of the bandits from the western Georgian province of Guria at the turn of the 20th century. Sisona Darchia, Simon Dolidze, Datiko Shevardnadze are main characters in this story, and their deeds are recounted in numerous ballads, stories and songs. They were as popular as Robin Hood in their time.

The film is based on real events, as described in letters written by a certain Kirile Chavleshvili to the notorious American bandit Henry Starr, with whom he apparently robbed a train in 1893. Although Starr and the other robbers were arrested, Chavleshvili managed to leave America. While in America he participated in Buffalo Bill Cody’s famous Wild West Show. He and other Georgian trick riders were advertised as “Russian Cossacks” and demonstrated daredevil horse riding techniques.

RIDERS OF THE WILD WEST

Documentary film. DVD. Approx. 30 min.

Author: Irakli Makharadze

1997

Georgian riders from the province of Guria made their first appearance in Buffalo Bill Cody’s “Wild West Show” in London in 1892, then arrived in America in 1893. Unfortunately, they were called “Russian Cossacks,” probably because Georgia was then part of the Russian Empire. Over the next thirty years, Georgian “Cossacks” made numerous appearances in Buffalo Bill’s ensemble, as well as other circuses and shows. The whole world came to know them, and even cowboys were impressed. According to Dee Brown, historian and researcher of the Wild West, the Georgian Cossacks transformed rodeo horse riding. “Cowboys were fascinated by their stunning stunts and later they represented the tricks in their own way in American rodeo.” The Georgian riders’ technique and unprecedented tricks made them famous throughout America. The film presents the Gurian trick riders’ amazing history, as well as its sad end after the Soviet takeover of Georgia. Unique documentary footage and photo materials found in Georgian and American archives were used in the film.

Unless stated otherwise or obviously not the case, all the text and images on this website are © A.J.T. Bainbridge 2006-2010

Gmail: alexjtb