THE

Société française des transports

automobiles du Caucase

OR

Did you know there was a French bus company

running a regular passenger service between Tbilisi and Vladikavkaz via Kazbegi

as early as [some time between c.1895 and c.1914]?

Information on the company in the 1914 Baedeker

Baedeker's Russia, with Teheran, Port Arthur and Peking—A Handbook for Travellers (published in 1914 in London by David & Charles Newton Abbot and George Allen & Unwin; available online here) was the first comprehensive guidebook to the Caucasus in the English language. (The original German-language Baedeker to Russia was published in 1895.)

The book lists hotels, contains much practical information, suggests sights to see and routes to follow, recommends restaurants, gives advice on how to haggle properly with the natives when purchasing souvenirs, details the exact cost of visits, meals and accommodation, suggests secondary day-trips, &c. &c.—everything one has come to expect from a modern guidebook to a place—and is beautifully illustrated with minute, perfect little maps of all the cities, towns and routes throughout the region.

The 1914 Baedeker's description of a journey from Tiflis (modern Tbilisi) in Georgia to the town of Vladikavkaz in (now) North Ossetia gives the following tantalizing information:

200 V. (132 M.), High Road. MOTOR OMNIBUSES of the Société française des transports automobiles du Caucase ply regularly from April 15th to Oct. 15th; they accomplish the journey in 10 hrs., starting at Tiflis from the office at Olginskaya 46 (Pl. A, 3; I), and arriving in Vladikavkaz at the Grand-Hôtel (fare 20 rb.; to Kazbek 15½ rb.; one pud of luggage allowed free, excess 2 rb. per pud). The company maintains hotels at Kazbek, Dushet, and Passanaur (dinner-station for passengers from Tiflis); the Mail Posting Stations are only for passengers by the mail. Private motor-car 125 rb.

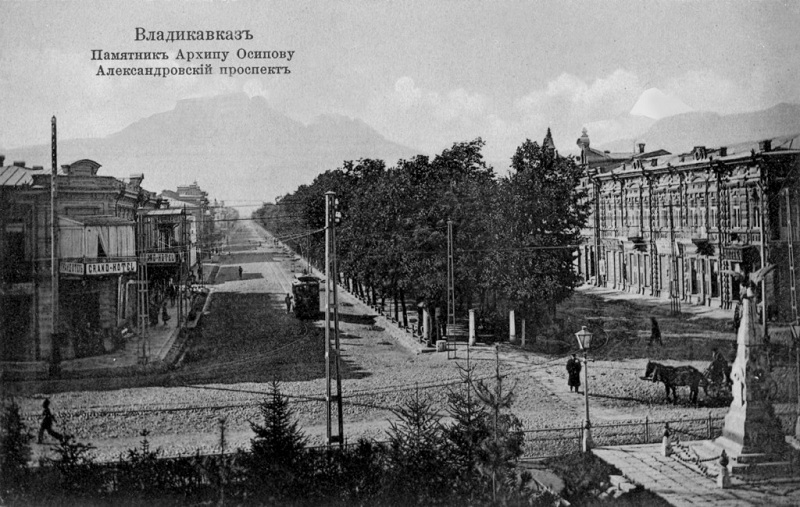

The guidebook then goes on to describe the journey in detail. From it, we may learn that in 1914 the Société ran: —1.—a bus station with a restaurant 'just short of Dushet'; —2.—another bus station in Pasanauri (with a "hotel-restaurant" this time; a room cost 1½ rubles and lunch 'from 1 rb.'); —3.—the Grand-Hôtel in Kazbegi (Stepantsminda; 'a dépendance of the hotel of the same name in Vladikavkaz, with a restaurant and view-terrace, R. 2-5, B. ¾, déj. 1-1½, D. 1½-2½, pens. 7-9 rb.'); and—4.—its parent, the no doubt grander Grand-Hôtel in Vladikavkaz (on the Alexándrovski Prospékt, 'R. 1½-6; D. (1-7) ¾-1½ rb.').

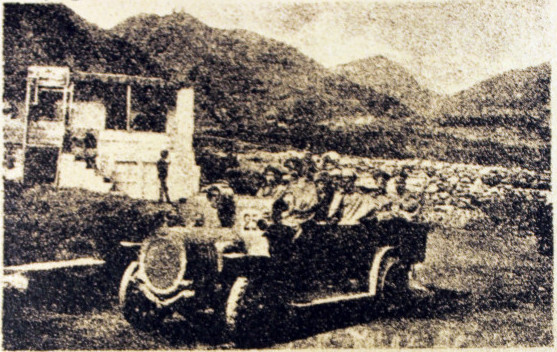

Charabanc no. 23 at Pasanauri

(A word on the Baedeker's prices)

The 1914 Baedeker guide to Russia tells us that £1 in 1914 was worth 9 rubles 58 copecks.

Using the currency converter on the website of the UK's National Archives (www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/default.htm), we can calculate that £1 in 1910 was worth £57.06 in 2005 and that £1 in 1915 was worth £43.06 in 2005.

The University of Illinois at Chicago's "MeasuringWorth" website (www.measuringworth.com) bases its calculations upon the Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to 2010; it tells us that £1 in 1914 was worth £68.80 in 2007 according to the retail price index (RPI; i.e. "the cost of living" index) and £360.15 in 2007 in terms of average earnings (i.e. "affordability").

So 1 ruble in 1914 was worth the equivalent of either roughly £5.20 in 2005 (National Archives currency converter) or £7.20 (2007; RPI) or even £37.60 (2007; average earnings).

This discrepancy makes calculating how much travel in the Caucasus cost in c.1914 in our (2013) money rather difficult:

According to the National Archives currency converter, the cheapest room (2 rubles) in Tbilisi's finest hotel—the London—in 1914 cost roughly £6.20 a night in our money, whereas the most expensive suite (10 rubles) would have cost the equivalent of about £62.

According to the University of Illinois at Chicago's "MeasuringWorth" website, however, which bases its calculations upon average earnings, the cheapest night in the London would have cost £75 in our money and the most expensive £376.

The latter figures seem much more credible, as the most expensive hotel room in the most expensive hotel in Tbilisi in 1914 would certainly have cost a lot more than £62 in our money: £376, on the other hand, seems about right. The problem, however, returns when we try to calculate the equivalent cost of e.g. a 2-phaeton taxi ride from Tbilisi's railway station to the town centre (75 copecks) or that of a journey by motor-car from Tbilisi to Vladikavkaz (125 rubles): it seems unlikely that first would have cost £28 (which would be daylight robbery nowadays) and the second could hardly have cost as much as £4,700 of our "average earning" pounds.

The figures we obtain from the National Archives' currency converter or by basing our calculations upon the retail price index now seem a lot more accurate: £3.90 or £5.40 respectively for the cab ride, and £650 and £900 for a car to Vladikavkaz (which sounds about right, considering what an extravagant luxury such a journey would have been at the time).

It therefore seems accurate to convert the 1914 prices of goods or services which rely upon "cheap" local labour (e.g. cab rides, buying burkas at the market, &c.) with the help of the National Archives currency converter, and to convert the prices of higher-added-value services (e.g. spending the night in expensive hotels and journeys by bus or car) with the help of the average earnings index upon which the "MeasuringWorth" website is based.

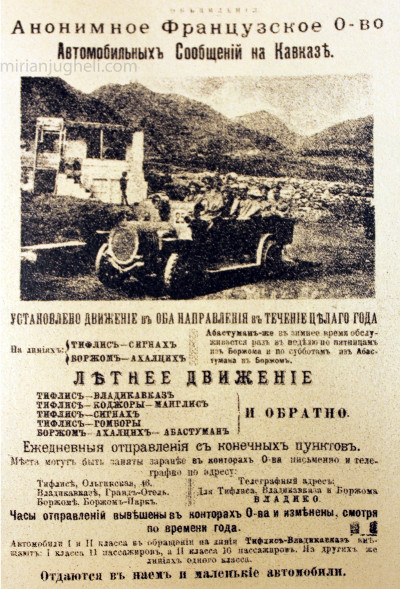

The promotional poster

|

|

|---|

Posters like this one would no doubt have been displayed around Tbilisi, particularly in the town's more expensive hotels and guesthouses, &c. From it, we can learn that besides running a service between Tbilisi and Vladikavkaz, the Société anonyme française des transports automobiles du Caucase also ran regular services (i) from Tbilisi to Manglisi via Kojori; (ii) to Sighnaghi; (iii) to Gombori (a very small town of some importance just below the Gombori Pass leading to Telavi); and (iv) to Abastumani via Akhaltsikhe.

(The map on the share certificate below, however, for what it is worth in terms of reliability, also shows other, more ambitious lines, viz. Tbilisi-Kutaisi-Poti and Tbilisi-Kutaisi-Batumi; Tbilisi-Baku; Vladikavkaz-Baku running along the northern flanks of the Caucasus Mountains; and even Vladikavkaz-Rostov/Don, Novorossiisk-Krasnodar-Piatigorsk and Novorossiisk-Krasnodar-Volgograd.)

Two views of the Grand-Hôtel in Vladikavkaz in the early 1900s

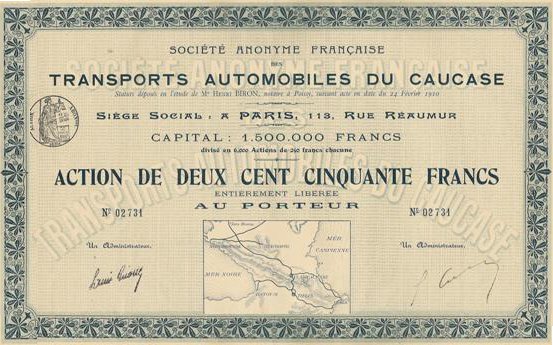

The share certificate

The société seems to have left almost no imagery behind whatsoever, and a trawl of the internet for photographs was largely fruitless. A rare exception is a small digital scan of a share certificate in the company to the tune of 250 French anciens francs, which reads:

Société anonyme française des Transports automobiles du Caucase

Statut déposé en l'étude de Maître Henri Beron, notaire à Poissy, [illegible] acte en date du 14 février 1910

Siège social: à Paris, 113 Rue Réaumur

Capital: 1,500,000 francs divisé en 6,000 actions de 250 francs

Action de 250 francs No. 02731 entièrement libérée au porteur

[Signed by two administrators]

The certificate also includes a map (in French) of the Caucasus showing the company's various routes viz. Batumi-Tbilisi-Baku, Tbilisi-Vladikavkaz, Baku-Vladikavkaz and further to the N.W. towards Novorossisk, Piatigorsk, &c.

(Note: 1,500,000 French Francs in 1914 would, according to the website of France's Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques, be worth 5 million Euros in 2013.)

The German newspaper article

Zwischen der Stadt Tiflis Transkaukasiens und der Stadt Wladikawkas Vorderkaukasiens (Bahnhof der Wladikawkaser Eisenbahn) verkehren auf der alten Georginischen Heerstraße (auch Grusinische Heerstraße genannt), die unmittelbar über das Hochgebirge führt, bereits seit Jahren staatliche Stellwagen (Omnibusse). Die Société Anonyme Française des Transports Automobiles du Caucase hat jetzt 30 Kraftwagen eingestellt, die vom 15. April bis zum 15. Oktober neben den staatlichen Stellwagen auf der Heerstraße zwischen Wladikawkas und Tiflis verkehren. Die Fahrt nimmt rund zehn Stunden im Kraftwagen, auf der Eisenbahn über Beslan, Petrowsk, Derbent, Baku und Elissawetpol etwa 42 Stunden in Anspruch. Für die Personenbeförderung mit Kraftwagen werden je 20 Rubel (etwa 43 Mark), für die Beförderung des Gepäcks 2 Rubel (etwa 4,30 Mark) für 1 Pud (16,38 kg) erhoben. Im übrigen verkehren jetzt auch zwischen Tiflis und einigen anderen Städten und Ortschaften Transkaukasiens Kraftwagen.

The last paragraph of "Eisenbahnen Transkaukasiens und der Kraftwagenverkehr auf der Georginischen Heerstraße", a short article published in the Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung (No. 44, Berlin: Wilhelm Ernst & Sohn, almost certainly 1913).

This article informs us that the Société ran around 30 vehicles, and that travelling by omnibus from Vladikavkaz to Tbilisi along the Georgian Military Road, which took around 10 hours, was a full 32 hours faster than the alternative by rail, which circumvented the Caucasus Mountains via Beslan, Petrovsk, Derbent, Baku and Elizavetpol.

The involvement of Schneider & Cie

A search for the Société française des transports automobiles du Caucase brought up a reference in an article entitled "Schneider, un acteur précoce de l'économie ouverte (des années 1900 aux années 1980)" by Catherine Vuillermot.

The article—which was published in BLANCHETON, Bertrand, & BONIN, Hubert (eds.), La croissance en économie ouverte (XVIIIe-XXIe siècles), Hommages à Jean-Charles Asselain, (Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang, 2009; reference to the Société on p. 361)—deals with the history of a French industrial company called Schneider-Creusot or simply Schneider & Cie, which was founded in 1836 and still exists as Schneider-Electric to this day.

In a paragraph on the company's early-twentieth-century expansion in an already increasingly globalized world, Vuillermot mentions that between 1912 and 1914, Schneider invested quelques capitaux in the Société française des transports automobiles du Caucase (among many other ventures):

Non seulement les commandes viennent de l’ensemble du monde, mais la société s’implante rapidement aussi dans des sociétés étrangères. Les premiers placements se font en 1878 et, moins d’une décennie après, le père d’Eugène II Schneider investit dans les Aciéries et fonderies de Terni en Italie. Au total, « Schneider & Compagnie commencent au début du XXe siècle à se muer en un groupe multinational ». Dans le contexte de l’alliance franco-russe, Schneider participe à un consortium pour créer la Société minière & métallurgique de Volga-Vichera, née en 1897, dont une partie se transforme en 1900 en Société des aciéries & chantiers de Paratov. Schneider fait une nouvelle tentative en Russie en vendant sa technique à Poutilov en 1907, à la Société Baranovsky (fusées) en 1909, à la Société russe pour la fabrication de munitions et d’armements en 1911 afin d’obtenir des commandes. En 1912, à la stratégie de conquête de marchés par vente de la technologie s’adjoint celle de la multinationalisation par achat de titres de sociétés russes. Schneider participe au rachat des Chantiers & ateliers Nevski qui sont ensuite cédés à Poutilov, ce qui lui permet de devenir actionnaire de cette dernière. Entre 1912 et 1914, Schneider place aussi quelques capitaux dans la Société Baranovsky, la Société russe pour la fabrication de munitions et d’armements, mais aussi dans la Société russe de constructions (travaux publics du port de Reval), la Société russo-baltique (chantiers navals à Reval), la Société pour la construction des wagons, les Transports automobiles du Caucase et prend une participation majoritaire dans la Société russe d’optique.

A brief description of the company in 1913

Found in Maurice Rondet-Saint's Aux confins de l'Europe et de l'Asie (Paris: Plon, 1913, pp. 329-330):

Nous devons signaler, à Tiflis, une initiative française des plus dignes d'intérêt; c'est la Société anonyme française des Transports automobiles du Caucase. Le conseil d'administration de cette Société, au sein duquel figure un conseiller d'Etat à Saint-Pétersbourg, est composé de personnalités françaises de haute honorabilité.

Lors de notre passage à Tiflis, cette Compagnie assurait par automobiles de 40 H.P., construites au Creusot, le trafic direct de Tiflis-Vladicaucase, soit 213 kilomètres à travers le Caucase, en 9 heures. Elle avait obtenu cette concession, en concurrence avec une compagnie allemande.

Ses résultats ayant récompensé l'initiative de ce service, la Compagnie a décidé d'intensifier son trafic. Devant son succès, elle a reçu en haut lieu l'assurance qu'un monopole et une subvention importante lui seraient acquis, dès la mise en exploitation, pour le service postal à effectuer entre Tiflis et Vladicaucase.

(Oct. 2018:) 'By car over the Caucasus' from Tbilisi to Vladikavkaz.

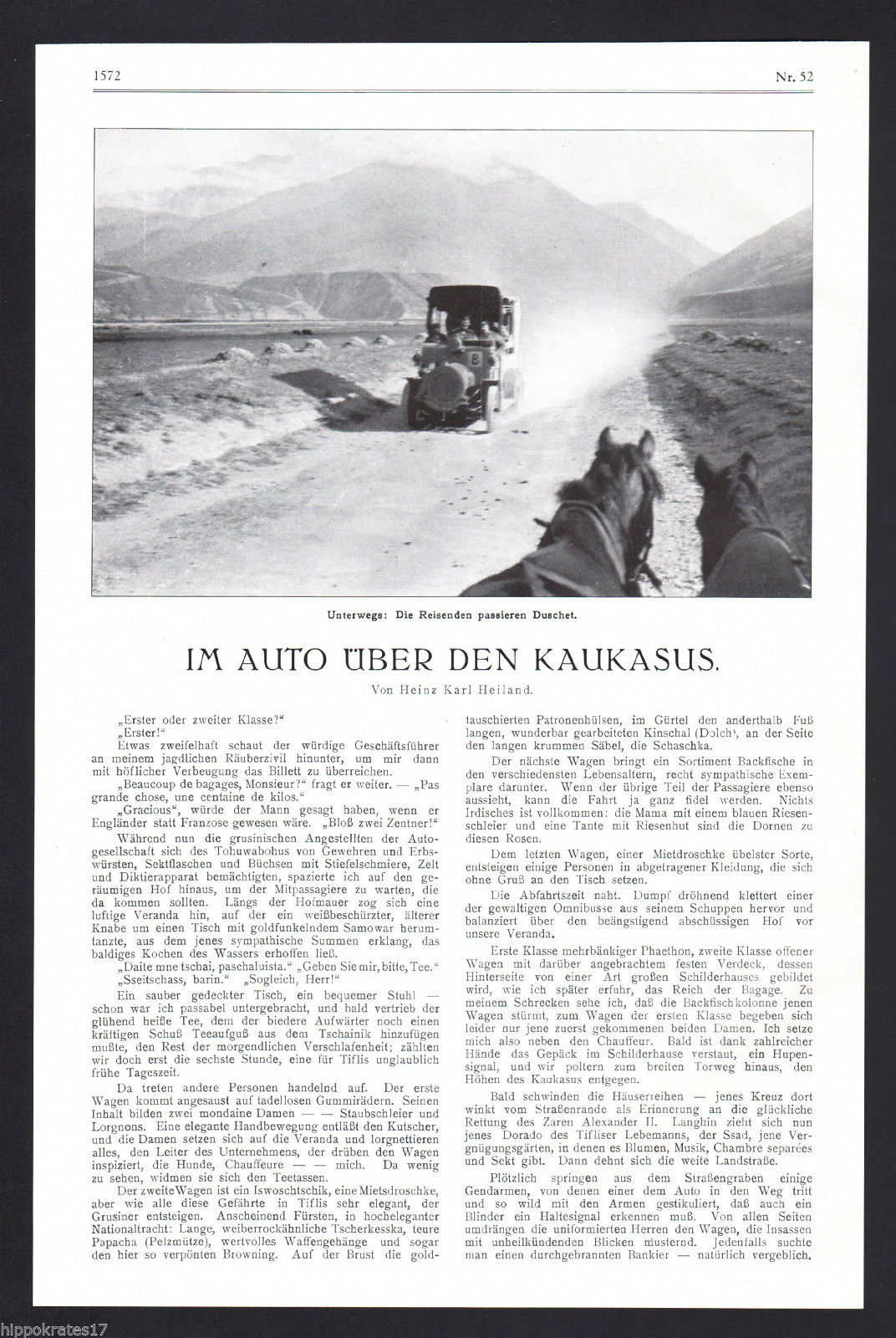

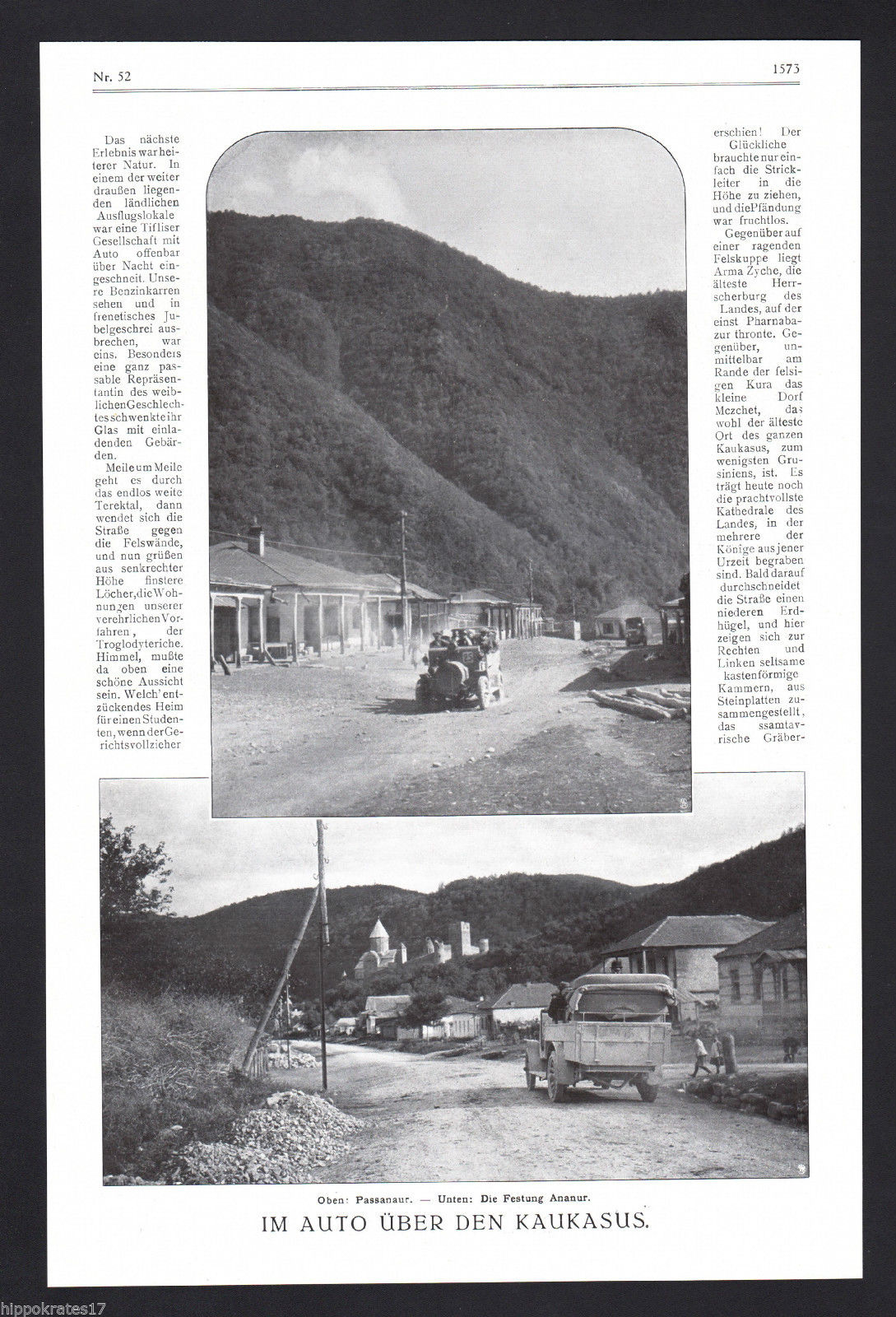

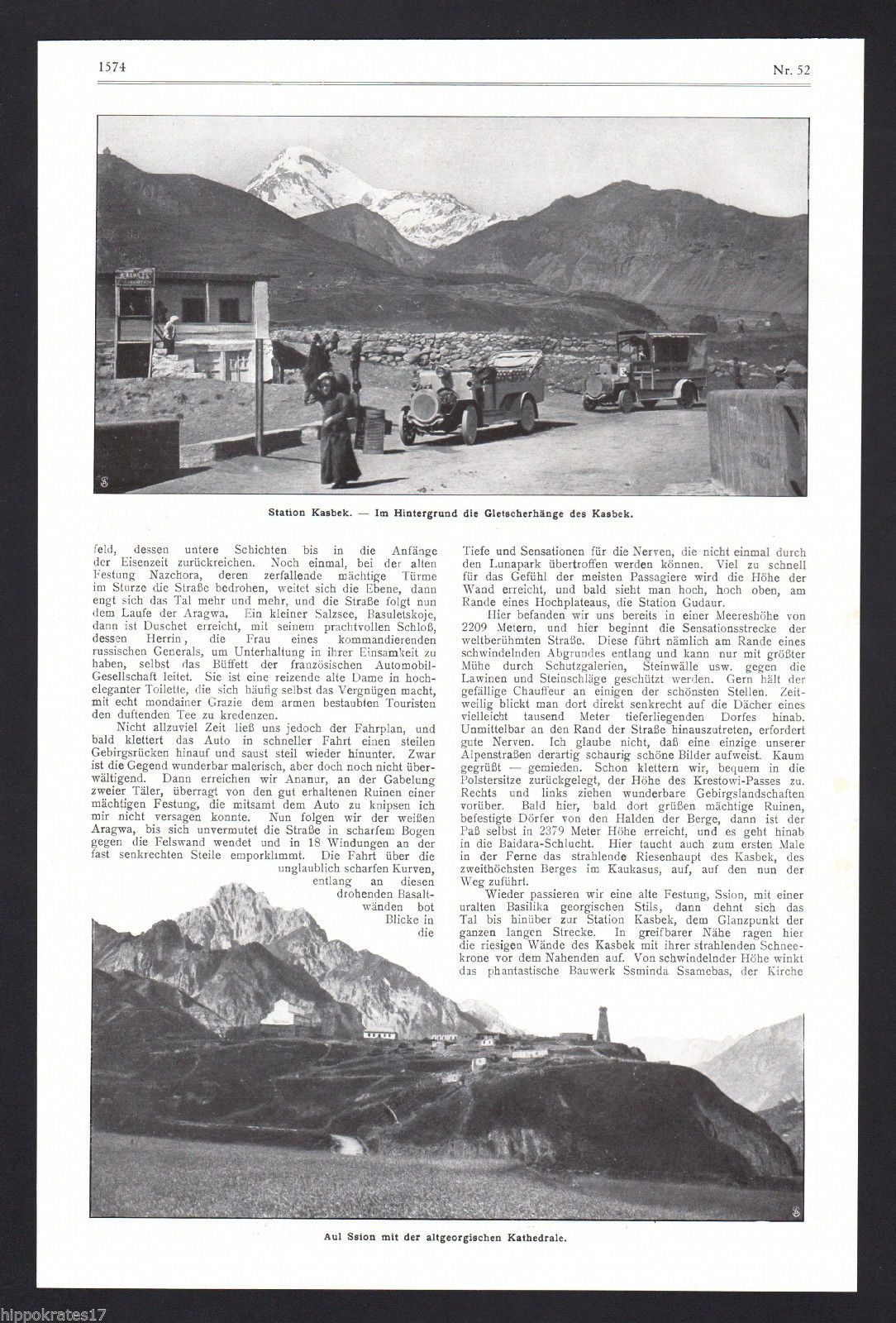

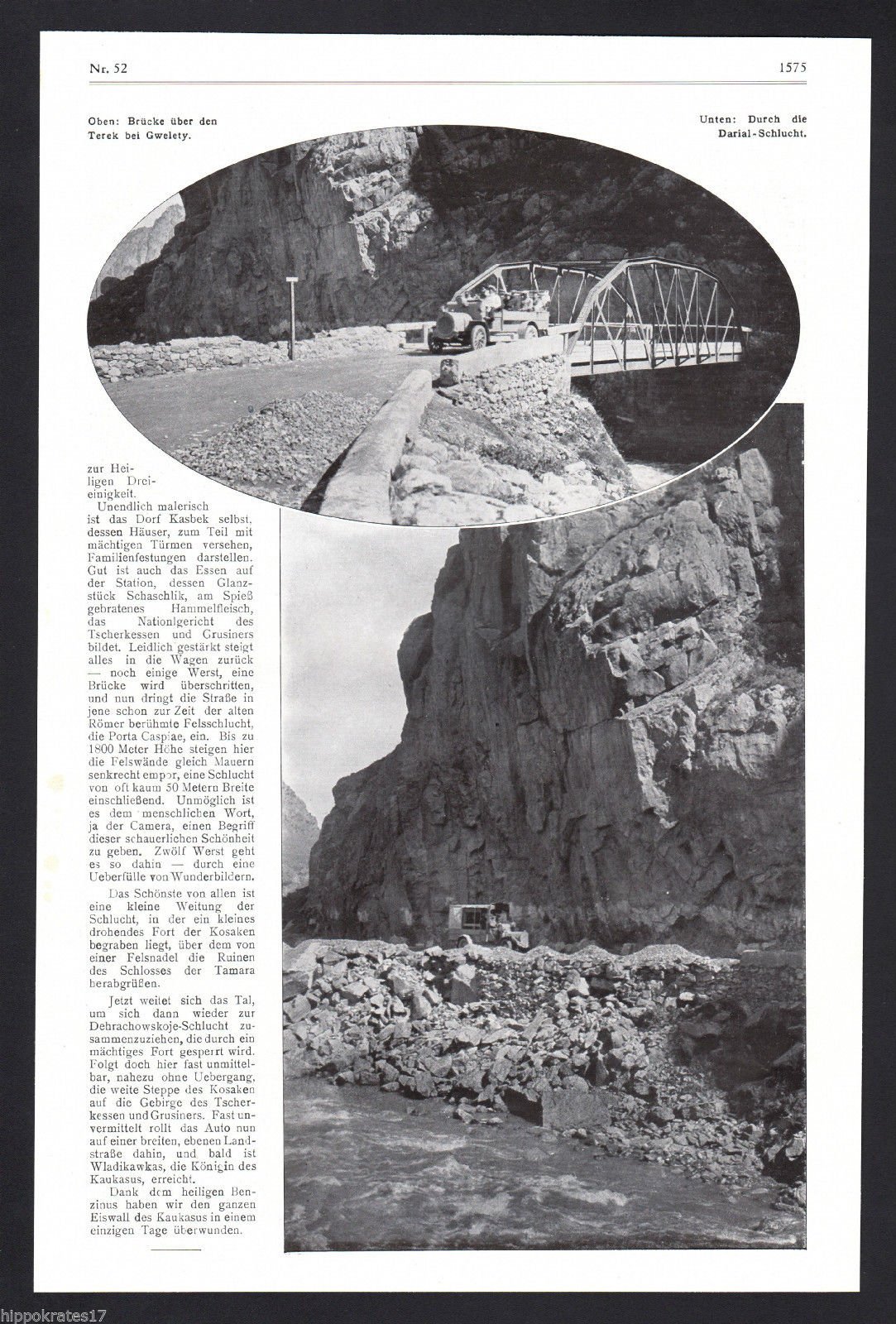

'Im Auto über den Kaukasus', by Heinz Karl Heiland, was published in an unknown German magazine in 1911. The text of the article itself contains almost nothing of interest besides a few vignettes, but was illustrated with several rather wonderful photographs of two petrol-engined charabancs (one for baggage and a lower class of traveller) puffing along the Georgian Military Highway (please click for larger images):

|

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

Unless stated otherwise or obviously not the case, all the text and images on this website are © A.J.T. Bainbridge 2006-2014

Do get in touch! Gmail: alexjtb