Zezvaoba

AN ANNUAL HORSE RACE

First and second place, Zezvaoba 2011

2011 © Daniel Nitsch

Zezvaoba (Georgian: ზეზვაობა) is a festival held every year on the last Sunday of May in the Tush villages of Zemo- and Kvemo-Alvani on the plain of Alvan in Georgia's eastern province of Kakheti. The festival and its horse race honour the memory of Zezva Gaprindauli, a warrior who led the Tush in battle alongside Georgian armies to defeat the Persians at the battle of Bakhtrioni in 1659.

Historical origins

The following is an account of the battle of Bakhtrioni (copied from the website of the Orthodox Church of America, of all places):

In the 17th century the Persian aggressors razed churches, monasteries, and fortresses and drove out thousands of Georgian families to resettle them in remote provinces of Persia. The deserted territories were settled by Turkic tribes from Central Asia. In the chronicle The Life of Kartli it is written: 'The name of Christ was not allowed to be uttered, except in a handful of mountainous regions: Tusheti, Pshavi, and Khevsureti.'

But the All-merciful Lord aroused a strong desire in the valiant prince Bidzina Choloqashvili of Kakheti and, together with Shalva and his uncle Elizbar, princes of the Aragvi and Ksani provinces, he led a struggle to liberate Kakheti from the Tatars. (The Persian governor of Kakheti, Salim Khan (ruled 1656–1664), had been encouraging the Tatar tribesmen to profane the Christian churches.)

Fearing that the enemy, who had already conquered Kakheti, would soon move in and also dominate Kartli, the princes Bidzina, Shalva, and Elizbar united the forces of those two regions in preparation for the attack. After much deliberation, Bidzina announced his intention to his father-in-law, Prince Zaal of Aragvi. Zaal’s soul was spiritually pained by the countless misfortunes and injustices his country had suffered, and he quickly pledged his support for the effort. He agreed to participate in the insurrection anonymously, while the Ksani rulers Shalva and Elizbar would command the armies.

On the moonless night of September 15, 1659, the feast of the Alaverdi Church (The feast of St. Joseph of Alaverdi) the united army of all eastern Georgia assembled and crossed over the mountains, past the village of Akhmeta, and launched a surprise attack on the Persians from Bakhtrioni Fortress and Alaverdi Church. The invader’s armies were so utterly crushed that their leader, Salim Khan, the Persian governor of Kakheti, barely succeeded in escaping from the avengers, after he had abandoned his family and army.

The victorious Georgian army offered prayers of thanksgiving to the Lord God and Great-martyr George, the protector of the Georgian people, who had appeared visibly to all during the battle, riding his white horse like a flash of lightning and leading the Georgians to victory.

And here is a even more romanticized account of how the Tush came into possession of the plain of Alvan: The Tale of Zezva (one of the Caucasian Legends translated from the Russian of A. Goulbat by Sergei de Wesselitsky-Bojidarovitch, New York: Hinds, Noble & Eldredge, 1904)

Two horsemen were giving chase to some wild goats. Quickly did their most daring horses run, but still faster did the light little goats save themselves by flight, jumping across narrow gorges with one bound, springing on small plateaus, and in a word as though favored with having wings they seemed to fly through bushes and low shrubs. Now, however, they made for a very high mountain covered with bushes and forests and rapidly found their way among green branches and blooming trees, ascending higher and higher. The pace of the pursuit of the horsemen considerably slowed down as the various plants were every now and then the cause of unexpected delays, while their victims, the goats, were able to catch breath between each long jump and thus got on rather well and without much difficulty. The comparatively large horses were of course forced to go out of their way in order to avoid knocking up against trees, which barred the trail, and even where the grass had been smoothed out the animals went rather quietly and the energetic horsemen saw themselves more than once obliged to cut and bend down massive branches which formed the chief impediment in the whole undertaking. When after long and renewed attempts they safely reached the summit of the mountain, the goats had completely disappeared, and looking in various directions in order to discover the hiding place of the fugitives, the plucky horsemen cast their glances at that part of the mountain at the foot of which spread itself out like a fairyland the perfectly magnificent valley of Alazana. And how beautiful she looked on this rare sunny day, all shining with soft sweet rays, separated from each other by a large number of various colored shades, one more perfect and exquisite than the other. Now she would seem to take a bath in some pale, rosy waves, produced by an unknown marvellous battery of light, then again she so dazzled in precious gold and finally blazed with emeralds and the branches of its quite innumerable vineyards. There was also the sea of clusters, which could be distinguished through its little fruit garden, and like gigantic flower bushes they concentrated in themselves an amazing variety of flowers from the very most conspicuous to the darkest and palest. In astonishment did the hunters stop. Till then none of the Toushines had known about the existence of the highly blessed and favored Kakhitia. Being illuminated and showing all of her blinding beauty, she indeed seemed to them a perfect paradise and attracted forever their exultant glances. And the hunt and goats and everything else was forgotten. They stood there in perfect adoration of this unusual perfection of beauty and being unable to resist any longer the force which drew them nearer and nearer to the happy land, they descended into the gorge of Pankisse. On the River Bazzarisse-Tskali they chanced to come upon a detachment of Tartar frontier guards, who immediately surrounded the newcomers, and having dealt with them in the most insulting and truly shameful manner, again chased them into the mountains from which they had come.

Arriving at home, the indignant Toushines made a halt near that river, where the nation usually assembled when it was necessary to decide some important affairs. Here did they also announce the facts of their perilous adventure and demand a revenge. Soon by the summons of the Elder there came together not only the Toushines, but also the Pchaves and Kersourians, called in to give their advice. They all unanimously decided to take terrible revenge for the insult inflicted on their countrymen. The Pchaves and Khevsourians promised their assistance and with general consent the whole army was divided into two parts. One division was to conceal itself in the gorge of Pankiss, while the other should direct itself towards the Baktrionan fortress, which was situated to the east of Alazana and was in those remote times considered a very powerful fortification. Nowadays we can judge of it only by its ruins, which, however, all testify its past grandeur and mightiness. It was impossible to cross the river otherwise than over the bridge, which the sly Tartars covered with ashes in order to always find out the exact number and direction of new arrivals. But this ingenious slyness was not long hidden from the searching eye of Zesva, the valiant leader of the detachment. He ordered to stop the horses near the outer gates and, riding at full speed across the bridge, he succeeded in hiding himself in a valley before the Tartars found time to appear. The latter, guiding themselves by the direction of the traces, started in pursuit of their antagonists, but with every step getting farther and farther away from those to capture which was their intense desire. In the meantime the night came on and, profiting by the darkness, the Toushines reached the foot of the very fortress without being noticed by anyone. Having ordered his warriors to rest, Zesva, without breaking the silence, took up a hammer, covered it with cow-hair felt, unloaded from his horse a very large maprasha (i.e., a pair of sacks tied unto the steed) filled with strong iron tusks and knocked the first great nail into the battlements of the fortress, and standing upon it and reaching as high as possible he made a second one stick, and thus he continued until he had made himself a kind of ladder of iron hooks to the tip-top of the high rampart wall, whence he jumped down and in a flash threw open the heavy gates. Like a rushing stream did the Toushines make their way into the fortress, while the first rays of the rising sun were falling upon the grim old fortifications. The Tartars, half asleep, ran out into a field, but in vain for now they were met by the Pchaves and Khevsoures, who had ventured out from the gorge of Pankisse. The Tartars, surrounded on all sides, were exterminated to the last one and the field of honor of Allavanne, on which the glorious fight had taken place, was from now on known under the name of "Gatzvetila" (from the word "gatsveta"—"they are killing").

The magnanimous and lion-hearted Zesva handed out all the rich booty of this ever-memorable day to his faithful allies, i.e., the Pchaves and Khevsoures, while Gatzvetila became the common property of all Toushines. Nowadays this historic spot is known under the designation, "Field of Allavanna." Some people pretend that this name comes from the Georgian word "ali," i.e., "flame," as on this field, after the fire of the battle, the Tartar blood went on smoking for a long time; others say this name originates from the Kshtinskian words "al"=vladyka and "va"=here. This latter supposition, it seems to me, must be nearer in approaching the truth, as Allvani was one of the country palaces of Tamara, the ruins of which were not kept, although traditions confirm the existence of a palace on the above-mentioned field.

Essentially, the story has it that, following the (shortlived) Georgian victory, the grateful princes of Kakheti and of the Aragvi and Ksani Gorges — to whose aid Zezva and his men had come — asked Zezva how they could reward him and his men, and offered them gold, weapons, or land. Zezva asked for land in the lowlands, to provide winter pastures for the many flocks of sheep his people bred, upon which the Georgian princes decided that all the land Zezva and his horse, Saghiri, could encircle at a gallop would be granted to the Tush in perpetuity. Setting out from Bakhtrioni, Zezva and Saghiri galloped as far as Takhtis Bogiri (near the village of Laliskuri), where Saghiri — exhausted from the battle — finally collapsed and died.

This land "belongs" to the Tush to this day, and is centred upon the villages of Zemo- and Kvemo- Alvani. Initially pastures where the flocks of Tush sheep would escape from the harsh winter in the high mountains of Tusheti, the plain of Alvan was later settled by the Tush when they emigrated from their mountain fastnesses in the early to mid-nineteenth century.

N.B. The victory was shortlived, for the leaders of the Bakhtrioni uprising — Zezva Gaprindauli, Bidzina Choloqashvili of Kakheti and the eristavis (dukes) of Ksani, Shalva and Elizbar — were later summoned by the vengeful Persians, who had them blinded and put to death.

The festival

Zezvaoba is essentially a typical provincial fête, and could be described as bearing all the hallmarks of a fair in a market town viz. entertainment (singing, dancing), competitions (the horse race, but also wrestling, arm-wrestling, boxing, &c.), commerce (local handicrafts on sale e.g. carpets and feltwork, food stalls), &c. The festival also fulfills a useful social function i.e. it presents an opportunity for people from neighbouring villages in the region to meet. In attendance are not only Tush, but also local Kakhetians and Pshavs, as well as (Muslim) Kists from the Pankisi Gorge. The horse race also seems to be open to anyobdy, although the riders seem to mostly be of Tush and Kist origin (Pshavs and Kakhetians being perhaps less well represented among them).

The motley crowd in Kvemo-Alvani for the 2011 edition of Zezvaoba

2011 © Daniel Nitsch

Traditional Tush songs performed by the 'Keselo' ensemble

2011 © Stefano Bertolini

Perhaps not quite so traditional: boxing for children

2011 © Stefano Bertolini

The festival of Zezvaoba does, however, have one particular and little-known feature which probably distinguishes it from most other village fêtes: it is not limited to the one village of Kvemo-Alvani, but is actually spread out across three different places viz. ceremonies also take place in the neighbouring village of Zemo-Alvani a few kilometres to the west and in a place called "Takhtis Bogiri" (Georgian: ტახტის ბოგირი, literally "the rope bridge of the bed") a few kilometres to the east. In order to explain this geographical division of the festival, we first need to provide an account of the horse race itself, of its origins, purpose and organization.

Doghi — more than just a horse race

2011 © Daniel Nitsch

The central event of Zezvaoba is, unsurprisingly, the exciting and sometimes dramatic horse race (Georgian: დოღი, "doghi") around which the entire festival is held. But this is, however, no mere race in the ordinary sense of the word, but a funerary horse race i.e. a funerary ritual held to honour (the long-deceased) Zezva Gaprindauli.

Doghi

The great French caucasologist Georges Charachidzé wrote at great length about the ritual of doghi in his prodigious Le système religieux de la Géorgie païenne (Paris: Maspero, 1968).

Readers wishing to read through his comprehensive, fascinating and lengthy description of such events can do so by consulting my attempted translation of the relevant chapter of his book (>>>link).

The doghi held for Zezvaoba can be divided into three main acts, the first one of which is itself divided into two parts:

1(a). A first dalaoba (Tush dialect of Georgian: დალაობა, from the Nakh i.e. Chechen and Ingush word dal, "god", to which the Georgian suffix "-oba" has been added), a ceremony of mourning held in Zemo-Alvani during which a delegation of riders from Kvemo-Alvani pay their respects to the souls of:

— Zezva Gaprindauli's maternal uncle, who was a Batsav (or "Tsova"), and thus belonged to a completely different (yet closely-related) clan than those of most of the other Tush, who are either "Chaghma", "Pirikiti" or "Gometsari" (these four names refer to the four different communities Tusheti, which are centred upon four different valleys);

— and, by extension, to the souls of those Batsbi ("Tsova") who died alongside their Chaghma "brothers" at the battle of Bakhtrioni;

1(b). The ritual blessing of the horses and riders who are to take part in the race. This is accomplished by the riders being offered to symbolically partake of the food and drink laid out on several t'abla ("tables"). The riders accept the proferred horns or glasses of wine or homemade beer and drink them "bottoms up" after having pronounced an appropriate (often very brief) funerary toast (Georgian: შესანდობარი, "shesandobari", not to be confused with the more usual "happy" toast, G. სადღეგრძელო, "sadghegrdzelo"), and pour the last sips over the manes of their horses. The horses are also fed a symbolic amount of barley from the bowl thereof which was placed on the carpet, and small strips of white cloth are attached to their bridles, confirming their having been blessed (these strips of cloth also serve two more prosaic purposes: horses without such a strip cannot take part in the race, and attaching these strips also makes switching horses before the race more difficult);

2011 © Stefano Bertolini

2007 © Alexander Bainbridge

2007 © Alexander Bainbridge

Both these rituals are accompanied (indeed defined) by the singing of a remarkable dirge (a funerary song) characteristic of Tusheti called dalai.

Dalaoba and dalai

Dalaoba is a ritual held to mourn the death of a man, the defining feature of which is the performance of a dirge called dalai (Tush dialect of Georgian: დალაი). The dalai is sung by the male mourners lined up on their horses before a talavari (or nishani) — a carpet upon which have been ritually laid out the clothes of the deceased, as well as objects which the soul will need in the afterlife (food, drink, salt, wool for clothes or to symbolize the flock of sheep of the deceased, barley for his horse, &c.) — or one of the several t'abla (= tables) set up by different groups of mourners for the funeral of the deceased or commemorative ceremony thereof.

Robert Bleichsteiner, in his Rossweihe und Pferderennen im Totenkult der Kaukasischen Völker ('The Consecration and Racing of Horses in the Funerary Cults of Caucasian Peoples', in KOPPERS, Dr. Wilhelm (ed.), Die Indogermanen und Germanenfrage — Neue Wege zu ihrer Lösung, 'The Indo-Germans and Germans Questions — New Ways to their Solution', Institut für Völkerkunde an der Universität Wien, Salzburg-Leipzig: Verlag Anton Pustet, 1936, pp. 461-7), gives an account of dalaoba and dalai in his description of a traditional Tush funeral:

As with the Khevsurs, the dying person may not stay in the house, and is instead placed in the courtyard regardless of the weather. The body is left there for two days and two nights. By its side are placed a cup of rock-salt, white wool and vodka. The women sing laments. In earlier times, as with many other Caucasian peoples, the widow was not allowed to express her sorrow in this manner, as it was considered shameful for her to do so. The person responsible for watching the body during the night was given a საშუაღამო გორდილა ("sashuaghamo gordila" — "midnight gordila) [note: a "gordila" is a lump of dough boiled in water instead of baked in an oven, a traditional way of preparing bread, particularly for Tush shepherds who had no access to a bread oven], a handful of roasted hops (Georgian: ბიჭონი — "bich'oni") and a drinking-horn full of vodka. The men come to lament the deceased early in the morning. In the old days, there were no coffins, and the dead were instead wrapped in a felt cloak before burial. At the head of the burial party walks a man carrying a bag with offerings of bread and vodka for the deceased. The grave is built of large flat stones, the coffin is placed inside it and it is then covered in earth. After the burial, all sit down to breakfast in the cemetery and drink to the memory of the deceased. When the burial party and guests return to the house of the deceased, the ნიშანი (Georgian: "nishani" — literally "sign") — the laid-out clothes of the deceased — is prepared. Alongside the clothes lie: hat, belt and dagger, socks, wool, salt and vodka. The women sit down next to the nishani and sing lamentations.

In the house, the table of the "release of the mouth" (p'irsamshnilo sup'ra) is laid; the elder holds a horn with vodka in his hand, and says: "God rest your soul! O soul of [the name of the deceased]! As custom and tradition demand, your descendants have generously provided for you. You shall have an unendless bounty of food and drink in the other world! May you be wealthy in the other world, as long as the heavens and the sun exist! May your relatives — your sisters, brothers, and parents who preceded you, as well as your "orphan" dead, those who have no-one to remember them — be remembered according to your wishes and to your will. May no-one do you any harm, may no-one attack you. For as long as the ox ploughs the field, as the mill grinds, as dew falls from the heavens and as green springs forth, may God grant his soul rest. This I do confirm with my word, with the priest's book, with the mercy of Jerusalem!" All those present drink. Then the men eat first — the women eat at noon. The nishani is brought into the house at sunset at laid out on a bed, where it will stay for a whole year. The widow cuts a lock of her hair as a sign of mourning, and the men let their hair grow — in earlier days for one year, but now for only 20 days. There is no mention of the horse of the deceased in Mak'alatia's description, but a Tush lamentation speaks of "At the feet of the deceased stands Lurdjai ("the blue-grey" — which refers to a horse), two hold his reins, he stamps with his foot and awaits the master, who is late on his journey." From this premise one may conclude that the horse of the deceased is at least present during the ceremony of mourning.

As a sign of their mourning, women used to wear a khokhira (Georgian ხოხირა) — a long, narrow piece of metal weave, similar in appearance to chain mail, with a black tassel at the end — on the right-hand side of their dress. Girls wore the khokhira on their backs [Mädchen trugen das Khokhira über dem Rücken]. Every Saturday, the women would go down to the river, dip the tassel in the water, and say: "May God rest the soul of [the name of the deceased]!" After a year had passed, the women would bake three kotori (Georgian ქოთორი) [a round, flat pocket of dough filled with ? — A.B.], lament the deceased for the last time, and dispose of the khokhira outside of the village.

During a whole year, a mourning ceremony would be held on the first day of every month, ceremony for which a kind of porridge (Georgian პაპა — p'ap'a) would be prepared. Only women would take part in these ceremonies. The most important event held to commemorate the deceased was held at the end of this year of mourning — the "beer of the year" (Georgian წლის ალუდი — ts'lis aludi), during which a horse race (Georgian სადგინი or დოღი — sadgini or doghi) would be held. The chief mourner would invite the entire village to a great funerary feast [Leichenschmaus], and would brew beer, slaughter animals for meat, and prepare the feast. As "gifts" (Georgian მოსანიჭრედ — mosanich'red), relatives and friends would bring a cheese, a measure of barley, a cow or a sheep, up to five rubles in cash, &c. The nishani would be laid out in front of the house, and next to it would be placed several pairs of woollen socks, tobacco pouches, wool, rock salt, vodka and beer, roasted wheat, &c. The women would sit around the nishani and lament. Five riders would then line up in front of the nishani, and the dalaoba (Georgian დალაობა) would begin. The word dalaoba comes from dal, the Chechen word for the highest divinity i.e. God. The south Caucasian Svans also have a female divinity called Dal, the guardian of the wild. The leader of these riders — known as the modalave (Georgian მოდალავე) — places himself in the middle of the group and praises the deceased in song, the other riders repeating dala, dala, dala... in unison as backing to his song. During the song, those in attendance offer the riders horns full of beer, the riders pouring a small quantity of beer over their horse's mane before emptying the horn. When the song is over, the head mourner directs the riders to go to the village of the maternal uncle of the deceased. The riders pick up a flag (Georgian ბაირაღი, bairaghi, from the Turkish bayrak) and leave. Attached to the top of the flag are a scarf (Georgian ალამი, alami, from the Arabic 'ãlam, "sign, flag"), woollen socks, and a tobacco pouch. A carpet (and, if possible, a nishani) is laid out in front of the maternal uncle's house, and some barley is strewn over it. Next to it are placed salt, wool, socks, loaves of votive bread with meat, vodka and beer, a basin of milk, and flowers tied together with herbs.

When the riders arrive, they stick the flag in the nishani, repeat the dalaoba, and drink to the memory of the deceased (Georgian შესანდობარი, shesandobari). They then weave strips of white cloth into the horses' manes, give them a handful of barley, and sprinkle some milk over them. After a small meal in the maternal uncle's house, they pick up the flag and return to the village of the deceased, where the horse race will take place.

All the villagers can attend this horse race, and relatives of the head mourner who live in neighbouring villages attend with their own riders as a mark of respect. The horses which will take part in the race are thoroughly exercised and are dispensed from work. Some horses won over 50 scarves (alami). Before the race, the horses are fed with barley from the nishani, and strips of white cloth are woven into their manes. The flag bearer (Georgian მებაირაღტე, mebairaght'e) takes the flag from the nishani, gallops to the designated place where the race will finish, and sticks it into the ground. The medoghe (Georgian მედოღე) — an old man learnèd in the ways of horse races — ensures that the race is properly organized and carried out. The riders delegate the riding to young boys. The old man gives the signal to start the race. An observer stands next to the flag, and numbers the riders in turn as they reach the finish line. The scarf goes to the first to arrive, and the other riders are awarded (in order) socks, gloves (Georgian კურო, k'uro), and a tobacco pouch. The next five riders to finish are given a young sheep, which they divide amongst each other. The riders replace the flag by the nishani after the race, and next to it are placed a kodi (3 poods i.e. 48kg) of beer and round votive loaves of bread (khink'ali). [Note: Bleichsteiner is probably confusing khink'ali — a pocket of dough containing meat, similar to a ravioli — and kotori — a round, flat bread with filled with meat, cheese, &c. — A.B.] A short stick to which are attached small strips of red or white cloth and white wool is stuck into every loaf, and a piece of rock salt is placed next to them. The women seated around the nishani lament the deceased one last time, and the men sing the dalaoba again. The funerary feast then follows, with toasts drunk to the memory of the deceased. One used to present the horse of the deceased to the maternal uncle, and the clothes to poor relatives. One would sometimes also consult the soothsayer (Georgian მკიტხავი, mk'it'khavi) in order to find out whom the soul of the deceased wished one should give the horse to.

Target shooting (Georgian ღაბაღობა, ghabaghoba) marked the end of the festivities held for the "beer of the year" (Georgian წლის ალუდი, ts'lis aludi). The prizes were what was left from the nishani: wool, woollen socks, salt, a sheep. Prizes like the latter two — which one could not fasten to the target — were symbolized by small loaves of bread. The chief mourner nominated a mek'vle (Georgian მეკვლე) to set up the shooting field and a referee to award the prizes. One shot with bows and arrows, and the prize went to the man whose arrow hit it. Should several shooters hit a target, they must draw for the prize, but the winner of the draw must buy back the other shooters' share of the prize. A race was held instead of target shooting in some villages. Such races and shooting were only held for men who were at least nine years old when they died.'

The following is a recording of (most of) a dalai, as sung before the t'abla laid out for Zezvaoba (i.e. in Zezva Gaprindauli's honour) in front of the Soviet-era "House of Culture" in Zemo-Alvani in 2007.

The lyrics of the song are (apparently, and in Georgian):

დალაი თქვით, დალაი, მხედრებო!

დალაი! დალაი! ძნელია დალაობაი!

ბრალია, მეფე ერეკლევ,

შენი ულაშქროდ სიკვდილი!

დალაი! დალაი!

ჩვენ ნუვის შევატყობინებთ

მეფის ერეკლეს სიკვდილსა!

დალაი! დალაი!

ლაშქარს გიკითხვენ ლომები,

ომში არ წაგვიძღვებია?

დალაი თქვით, დალაი, მხედრებო!

დალაი! დალაი!

მტერთან _ ხმალამოღებულო!

ლაშქარს _ თავგამოდებულო!

დალაი! დალაი!

ჭკვიანო, საქცივლიანო!

გამბჭეო, მოსამართლეო!

დალაი! დალაი!

იმედო თავის ქვეყნისა,

გამრიგევ საქართველოსი!

დალაი! დალაი!

ნეტავ შენ, სულეთს შემსვლელო

მტრედისფერაის ცხენითა!

დალაი, დალაი ვთქვათ, მხედრებო!

დალაი! დალაი!

ძნელია დალაობაი!

With the exception of a few of these lines, I have, however, not been able to reconcile the recording of the dalai as performed for Zezvaoba with these lyrics.

The following picture shows the t'abla, as laid out in Zemo-Alvani in 2007. Note the enamel dish containing barley behind the t'abla, as well as the large plastic bottles of wine or homemade beer or both in the right-hand corner. (Photos © Alexander Bainbridge)

The same t'abla, as laid out in Zemo-Alvani in 2010 (salad and fish were included that year). Not visible in these photographs is mutton — grilled on skewers or boiled on the bone in chunks.

A remarkable cast iron stirrup (Batsbur: აბჟუნტ, "abjunt") has also been placed on the carpet (just in front of the dish of salad); the addition of a 2cm rim along its lower surface enables it to be used as a drinking vessel.

An older photograph of a "proper" talavari or nishani, as laid out in Tusheti. The clothes of the deceased occupy the most important position on the carpet, with symbolic amounts of food, drink and wool &c. having been placed next to them. (Photo © Georgian National Museums)

2. A second dalaoba, during which a delegation of riders pay their respects (either to the soul of Zezva Gaprindauli, or — possibly and most interestingly — to the memory of his horse Saghiri (= "small", "little"), i.e. the horse upon whose back he galloped across the plain of Alvan following the battle of Bakhtrioni — see above) in front of the Soviet-era monument erected at "Takhtis Bogiri" where Zezva Gaprindauli's horse finally stopped and died.

The dalaoba held for Zezvaoba at Takhtis Bogiri in 2009. Note the monument, and the t'abla (carpet) of food and drink &c. set before it. Photo © Giorgi Mamardashvili

(This ceremony is not, apparently, organized every year: it seems to be less spontaneous — and therefore perhaps "less traditional" — than the ceremony which takes place in Zemo-Alvani. In the author's experience, the dalaoba at Takhtis Bogiri has only been held when local government viz. the regional government of Kakheti and the municipal authorities of nearby Akhmeta takes part in organising an edition of Zezvaoba.)

3. The race itself, which begins at "Takhtis Bogiri" and ends in Kvemo-Alvani.

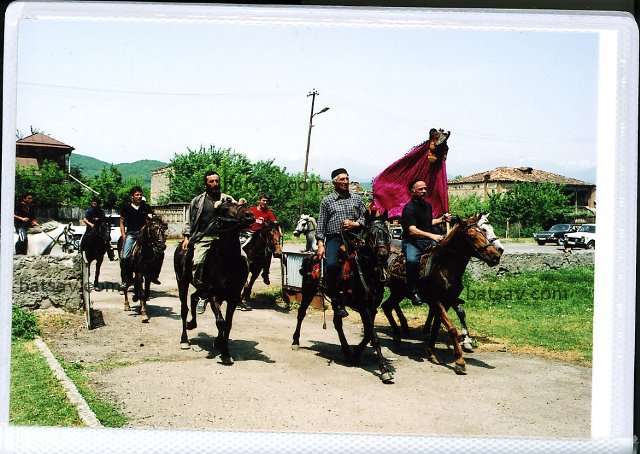

Dalaoba and dalai in Zemo-Alvani

A delegation of riders arrives in Zemo-Alvani at around midday, having ridden from Kvemo-Alvani (slowly, in order to spare those horses which are to race after the ceremony). They sing a dalai as they ride, and one of the riders holds aloft a purple banner (Georgian ბაირაღი, bairaghi, Batsbur ბერახ, berakh, from the Turkish word for flag, bayrak) which the Tush hold to be sacred (this is a pagan i.e. pre-Christian belief; for more information on this banner, see Charachidzé, op. cit., pp. 205-225).

The riders line up in front of the t'abla, and continue to sing their dalai, which is punctuated by their being offered food and drink, their horses being fed a symbolic amount of barley and being blessed by having small strips of white cloth being attached to their bridles, &c. (see above). The riders then slowly make their way back through Kvemo-Alvani to Takhtis Bogiri, where the race starts. In the meantime, those who wish to see the finish make their way (by car) to the centre of Kvemo-Alvani. An hour or so later, word of the riders' arrival begins to spread, and people line up along the road, positioning themselves as close as possible to the man holding the aforementioned banner.

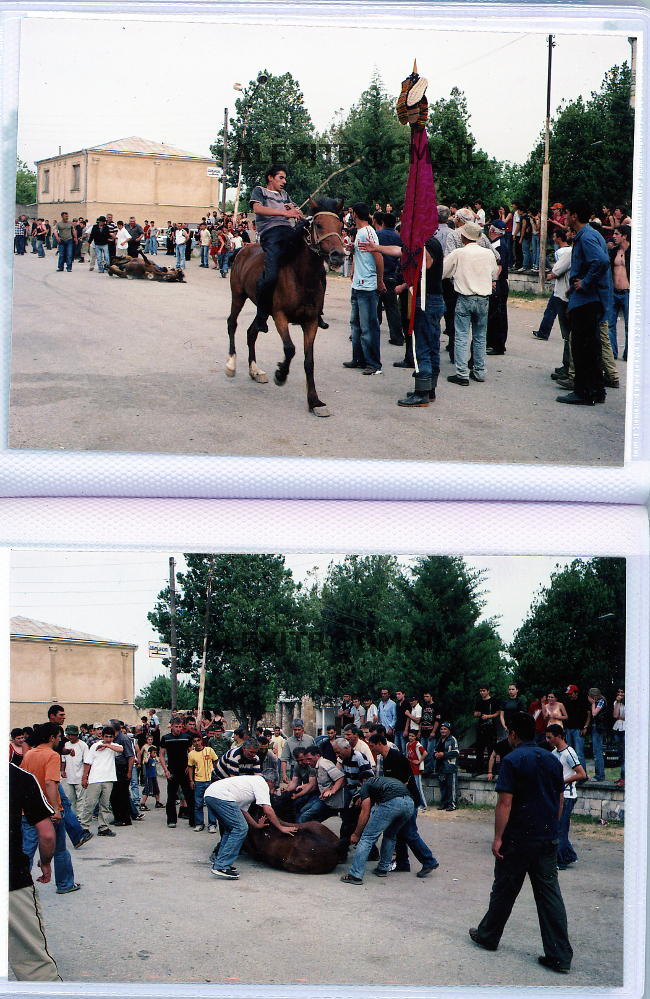

The race

The race covers a distance of approximately 3-4km. The finishing line is indicated by the holy Tush banner, which a man holds by the side of the road. The first rider to pass it wins the race (prizes are also awarded to second and third place).

Dito Gagoidze winning the 2011 Zezvaoba race (series © Daniel Nitsch)

The first rider to pass the banner receives the woollen socks which hung from the top of the banner's staff, a quite respectable amount of money in cash (? which the owners of the horses have pooled), a sheep, and the right to parade around with the banner in hand as well as the respect of all.

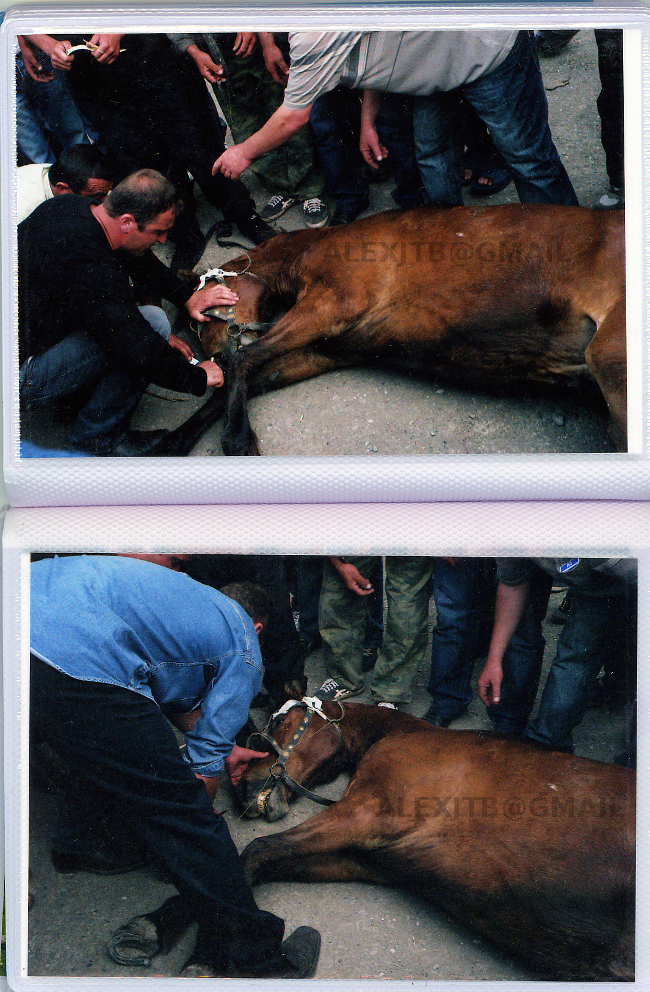

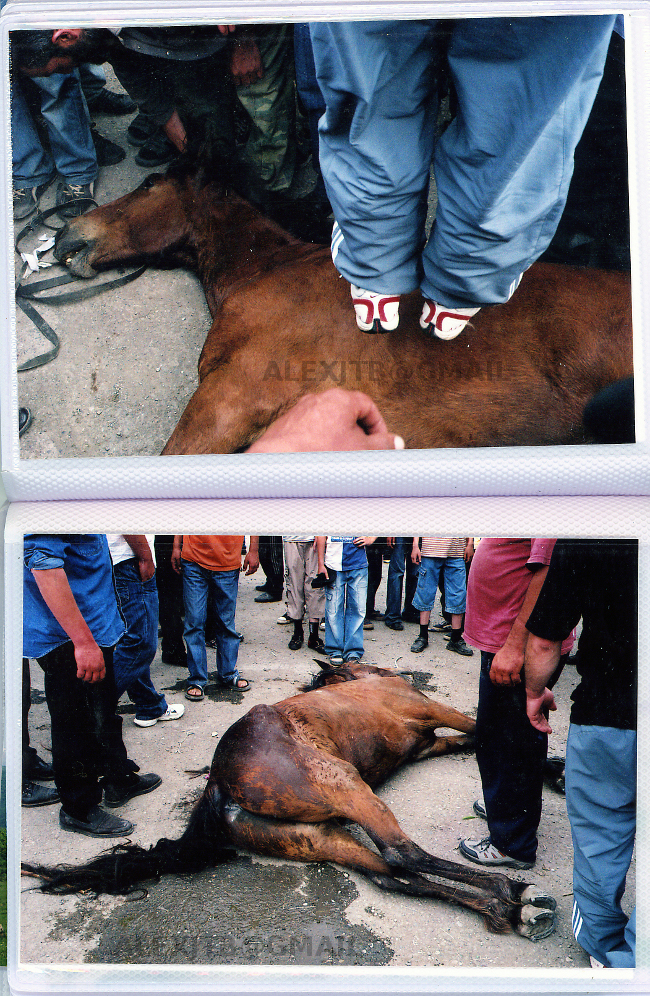

The race may seem short — barely a few kilometres long: a far cry from the 'race through the night' described in Blechsteiner and Charachidzé (op. cit., see above) — but it can prove to be too much for some of the horses taking part. Temperatures on the plain of Alvan in late May can already reach well over 30°C, and many horses are absolutely exhausted by the time they cross the finishing line. To the author's knowledge, there have, thankfully, been no fatalities since the horse that collapsed and died just before the finishing line in 2007. Attempts to reanimate it included poking an ear of wheat up its nose (presumably to "tickle" it into breathing again, or to ensure that its airways were open), poking the same ear of wheat up its urethra, a man inserting his arm (up to the shoulder) up the horse's rear, and jumping up and down onto its ribcage (the equine equivalent of cardiac massage). All these attempts were, unfortunately, unsuccessful, and the poor creature's body was unceremoniously taken away on the back of a lorry.

Unless stated otherwise or obviously not the case, all the text and images on this website are © A.J.T. Bainbridge 2006-2015

Do get in touch! Gmail: alexjtb